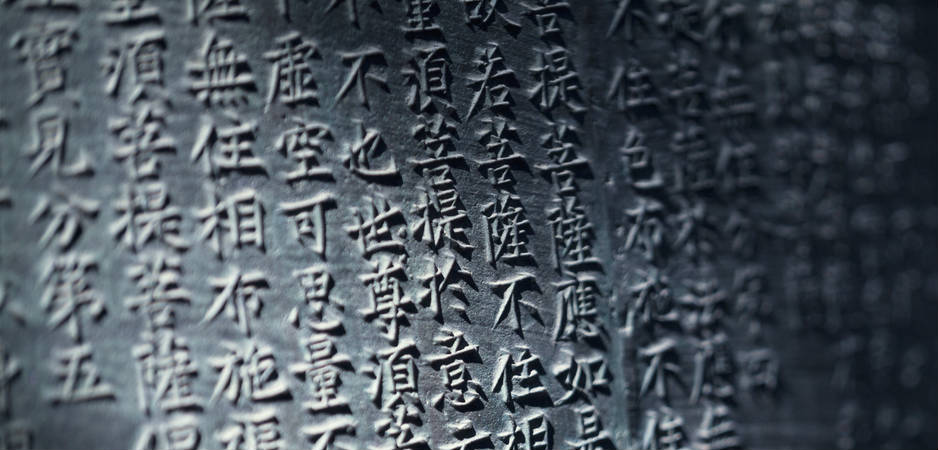

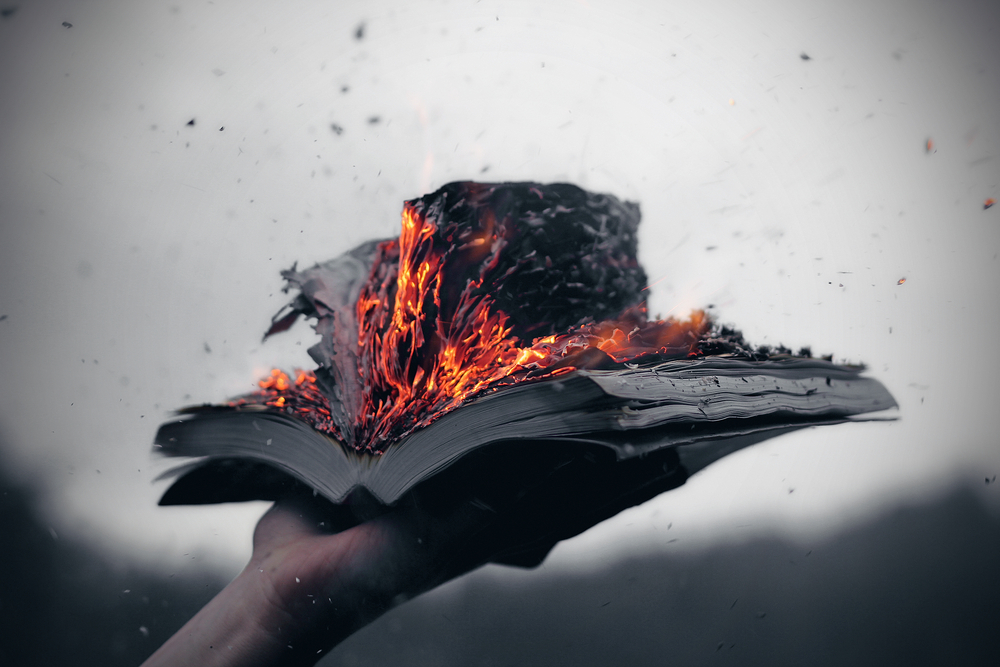

To protect against the burning of manuscripts, Chinese masters turned to engraving books on stone.

A New Yorker cartoon shows two men walking past the US Congress. One says to the other: “Hey, the Constitution isn’t engraved in stone.” True, but in China many important works are and, because they are, they have endured throughout that country’s history and been helpful to scholars outside its borders.

The man who united the provinces that became China, Qin Shihuang, ordered books to be burned. When he died in 210 BC, the Chinese found a more durable way to make — and preserve — the written word. They began engraving books on stone. And then to help disseminate the books, they encouraged people to make rubbings of the stones — an early form of a mass medium.

Centuries later, after Qin was buried, along with the terracotta warriors and other implements of security, the Chinese opened what is now known as the Museum of Steles in the city of Xian, which had been Qin’s capital.

Copying is Not Frowned Upon

The Museum of Steles claims it houses 3,000 stone records, both writings and paintings, which are rare and classic. They range over 900 years of Chinese history. Many are protected by glass, and rubbings are no longer made from them. One of the most memorable is the Dictionary of Terms, dated 222-226 AD and described on a nearby sign as: “China’s first monograph of the meaning of words, is one of the Confucian classic books. It is an important reference for textual researches of the meanings. It is also very valuable in the student of ancient China’s nature, geography and languages.”

A smaller tablet dates to 763 AD and “gives an account of how Zang Hualke participated in the resistance against the invading enemy of Xi, Shiwei and the West expedition in subduing the Turks as well as how he had been given posthuous (sic) ranks three times.”

Not only is the content important, but also the calligraphy. The calligrapher was Yan Zhenqing, then about 60 years old, whose style had matured, leaving the tablet as an important example in researching Yan’s calligraphy. Yan influenced calligraphers for many centuries after he died in 785 AD, in part because later calligraphers could study his works on stone or rubbings made from the stones he engraved. Calligraphy is an art form in China and imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Copying is not frowned upon.

Engraving books in stone continues in China today. On one of my visits, I saw a man engraving a large stone but instead of chiseling out the characters, he was using an electric saw.

Although the Chinese were not the first to engrave on stone, they were the first to appreciate its potential. Official edicts and literature were carved on stone and displayed in major cities. People were allowed to make copies of engravings, and in some cases the government had technicians available to make the copies — an early version of a government press. It also suggests government control of the message, of what was distributed and to whom. However, without a better record, one can only speculate.

Adventures in Retrieval

But all that rubbing comes with a cost. Eventually, the stone is rubbed nearly smooth or gummed up through over-inking, and precise copies can no longer be made. Fortunately, some very historical edicts have been preserved only because the paper rubbing still exists in some museums, and they have been useful to scholars in reconstructing what the original stone was like or in adding to the historical record of China. Wilma Fairbanks, for example, realized that rubbings were sometimes more useful because they were clearer than the original steles. In fact, she wrote a book about the experience aptly titled Adventures in Retrieval: Han Murals and Shang Bronze Molds.

The value of the engraved stones and preserved rubbings extend to scholars throughout the world. Two notable scholars were Marshall Broomhall and Joseph Needham, both British citizens. Broomhall had been a missionary to China and wanted to study the origins of Islam in that country. His best sources of information were rubbings, including one claiming to be a contemporaneous engraving of the first mosque in China. Although Broomhall doubted the date, he did not doubt the rubbing’s value to his research.

Needham produced the encyclopedic Science and Civilisation in China and illustrated various historical technologies with rubbings he had uncovered. In his discussion of the hodometer (today an odometer), he used a rubbing that shows a carriage drawn by two horses. In his discussion of astronomy in China, he reproduced a rubbing from 1247 that shows a planisphere. The original stone is located in Suzhou, encased in glass. At the top of the map, written in Chinese characters, it says: Star Map. It is evidence of early Chinese knowledge of astronomy.

Engraving books in stone continues in China today. On one of my visits, I saw a man engraving a large stone but instead of chiseling out the characters, he was using an electric saw. And at the Museum of Steles, one can watch the rubbing process and then purchase rubbings. But these are antiquated sidelights to modernity and have been replaced with printing presses.

China scholars owe much to the reaction to Qin Shihuang’s book burnings. As a communications scholar, Carolyn Marvin, once wrote: “The past really does survive in the future.”

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.