In Nigeria, close monitoring of the arts and literary scenes by authorities dates back to military rule.

When the film adaptation of Chimamanda Adichie’s literary masterpiece, Half of a Yellow Sun, was announced, many Nigerians cheered. For those who had read the book, it meant seeing Olanna and Kainene come to life. For those who hadn’t, it meant discovering what the fuss was all about. Detailing the sordid past of a bloody Biafra civil war, which had all but been obliterated from Nigerian history, the movie adaptation of the book promised to be an avenue of education for the teeming Nigerian public — particularly those born after the 1970s.

Alas, that was not to be. Since premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in 2013, the movie was banned in Nigeria until recently. The film, starring the BAFTA award-winning Chiwetel Ejiofor of 12 Years a Slave, was censored by the National Film Video and Censors Board (NFVCB), the Nigerian government agency for rating and vetting visual material. The condition given by the agency for placing the movie on consideration involved the removal of offensive scenes.

The reasons cited by censors for taking such a hard stance appear plausible enough. With the level of volatility, namely in the battle against Boko Haram, anything remotely fueling or adding to distrust among the country’s various groups could very well tip Nigeria over the precipice into a dark abyss. When one takes into consideration the fact that censorship of literary arts is fast becoming the norm, the banning of the movie might just be business as usual.

Protection of State and Religion

Over three decades of military rule meant that any growing dissent, the most vocal being the media, would have to be silenced at all cost. Thus, the press, journalists and writers have received the short end of the stick from different military governments in Nigeria. From the infamous Decree No. 4 of 1984 to threats and intimidation by the Babaginda regime, down to the oppressive Sani Abacha government, Nigeria’s press has been the target of punitive measures by state authorities. Targeted media houses were closed down with newspapers seized and journalists arrested or incarcerated without trial. Alongside other human rights activists, the list of detainees includes Professor Wole Soyinka, Nigeria’s first Nobel laureate, and Chief Gani Fawehinmi. With the advent of democracy in 1999, things seemed to have eased off for the press by way of state oppression, although not completely.

Nigerian society, like others in Africa, has always thrived deeply on high values and morals. Before the advent of colonialism, ancient Nigerian societies were governed by a strict code of morals, where members of the community were expected to act in a particular manner, show courtesy to elders in a distinct way, and worship specific deities as well as shun immorality, stealing and various other vices. Individuals who acted in ways contrary to those codes were publicly shamed, ostracized or banished from the village.

Free societies are those where individual citizens have the right to express themselves, be it in writing or whichever form … Censoring literary material is an infringement of freedom of expression.

With the adoption of Christianity in the south following colonialism and the spread of Islam in the north, religious bodies have since taken up the role of a moral compass, while Nigerians have adhered to their teachings with the same fervor a student would study his favorite subject. Thus, when literature or other material are found to be morally offensive to the religious tenets or beliefs of such institutions, there is usually an outcry that ends in state censorship being enforced.

Politicians have been known to take advantage of the strong pull that religion has on the average Nigerian. At various points in Nigeria’s history, religious riots have broken out in the northern part of the country, most often started and stoked by the anonymous publication of offensive material.

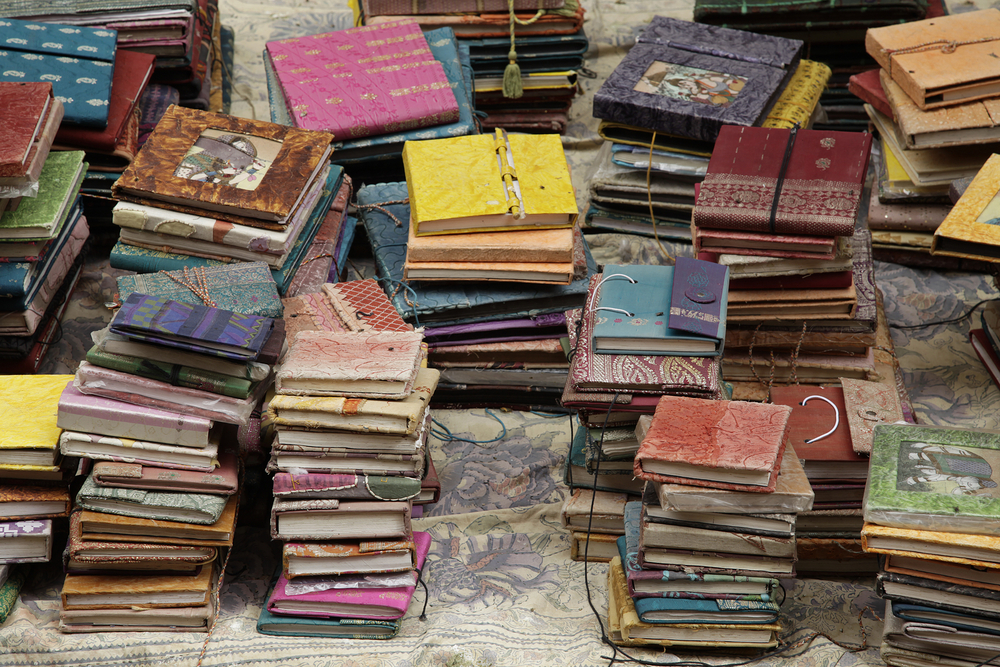

Books of Love

A popular market in Kano State’s entertainment industry is the Littattafan Soyayya, a literature genre literally translated as books of love. Written in colloquial Hausa, mainly by female writers, most of the books are based on love, romance and the contemporary lives of Hausa women, while others deal with social issues such as underage marriage, female education, the dangers of Vesicovaginal Fistula (VVF) and the spread of HIV/AIDS.

Expectedly, the biggest fans of the genre are women both old and young, married, single or divorced, and they eagerly soak up the love stories, drama and the general escapism that such novels give. However, given the conservative and male-dominated society of Kano State, these books have been frowned upon and are accused of corrupting the minds of young women.

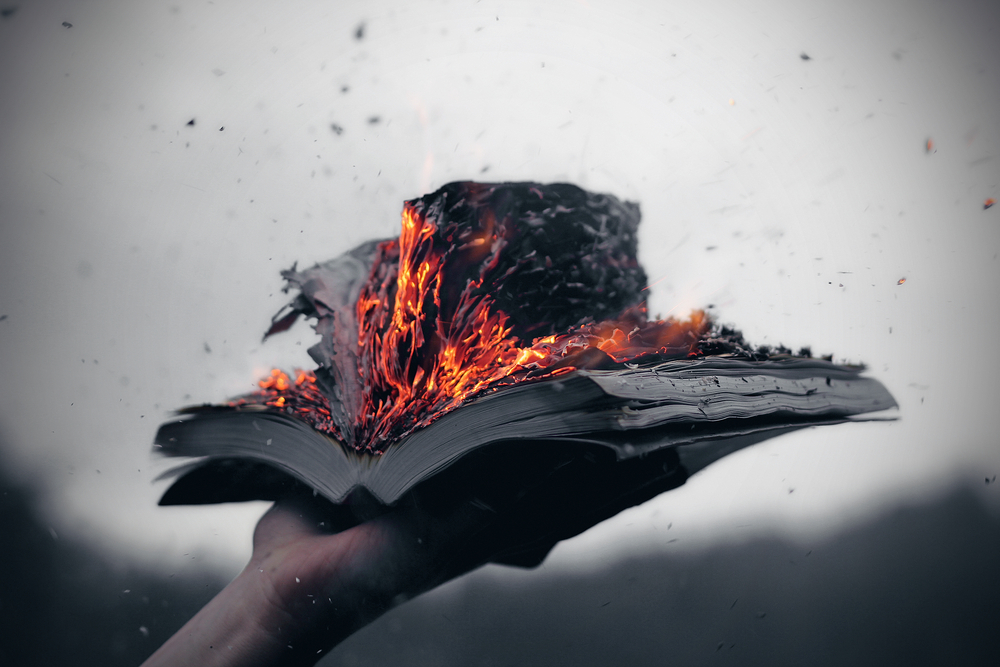

In June 2007, A Daidaita Sahu, a Kano state agency for the reorientation of society, declared these books to be immoral and organized a burning event at a local school. But authorities were not done yet. In August 2007, a set of stringent rules were laid down by the Kano State Censorship Board, requesting every writer to register individually in allegiance to it. Before publishing or releasing any book to the public, writers were now expected to seek approval first, so each page could be examined for offensive content such as intimate scenes between a man and woman or outright denouncement of polygamy. If any such content was found, a writer would be mandated to remove those portions before being allowed to go ahead and publish.

Writers went on strike in protest and the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) waded in. Through their assistance, a truce was brokered, with the Kano State Censorship Board relaxing its conditions and bringing to an end the impasse between writers and the state government.

Free societies are those where individual citizens have the right to express themselves, be it in writing or whichever form. It is also one where individuals should have access to whatever information they want or need. Censoring literary material is an infringement of freedom of expression as well as the right to information.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.