The importance of the issues surrounding banning books is that of fundamental freedoms and civil liberties.

Background

There is a humorous element to Alexander Woollcott’s famous quip that all good things are either illegal, immoral or fattening. If you look at the tradition of literary censorship, this postulation becomes less amusing, as it appears that every book worth reading has either been subjected to burning, banning or been challenged at some point in history. The Origin of Species, 1984, The Philosophical Dictionary, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, The Catcher in the Rye, Ulysses, Lolita, The Social Contact, Howl, All Quiet on the Western Front, The New Testament in Englyshe, and Gone with the Wind are only a few examples of a seemingly endless list of historical attempts at mind control.

…he who destroys a good Book, kills reason itself.

– John Milton, Areopagitica

Neuroscientists and linguists have long tried to deconstruct our relationship with words. Some, like the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, suggest that language shapes our thoughts and determines behavior — that, as the father of modern linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure tells us, speech is a social construct.

This symbiotic relationship between thought and expression is what makes a book such a dangerous object. On the one hand, it is the sum total of the author’s ideas, nurtured — or perhaps provoked — by his or her environment. On the other, these ideas will feed back into the social fabric and weave the infinite web of unpredictable potential. Once conceived, an idea can never be unthought, even if the word that signifies it can be silenced. Yet it is not for the lack of trying.

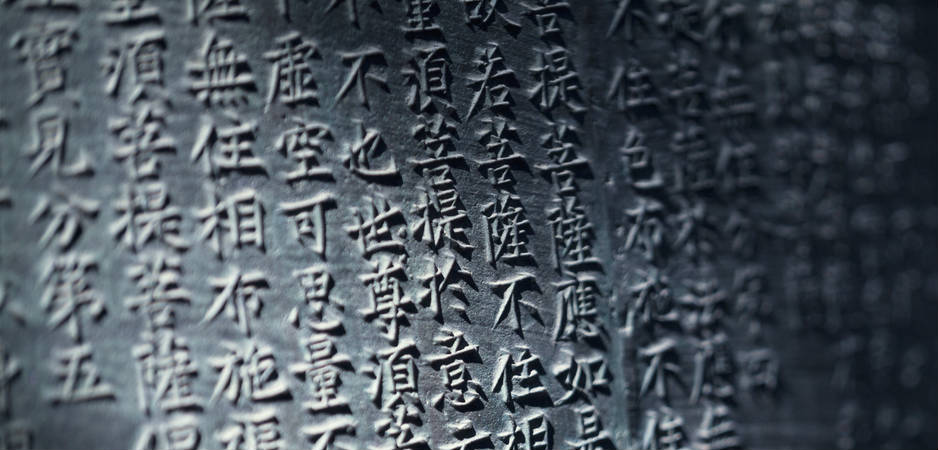

In ancient China, the Ch’in Emperor Shih Huang-ti had some 460 scholars buried alive for disobeying the order to burn the Shih Ching (Book of History) and Shu Ching (Book of Odes), at a time where books were thought to undermine dynastic authority and scholars were seen as “vermin” that could cast doubt upon the law of the time. Roman emperors started burning both Christians and their writings as heretical as early as during the rule of Diocletian. Pope Pius IV introduced the Index of Prohibited Books, Index prohibitorum librorum — a 500-page list that included names like Hobbes, Descartes, Hume, Voltaire, and was abolished by the Vatican Council only in the 1960s.

Voltaire had more books burned than any other writer in the 18th century, with at least ten different titles torched across Europe. Leftist writings, among them Bertrand Russell’s, were burned by Chiang Kai-Chek’s troops, while Mao’s Red Army exterminated what it defined as “parasitic” writing during the Cultural Revolution. The Third Reich had set up Brenn-Kommandos — arson squads targeting synagogues and libraries, with UNESCO estimating a loss of 15-22 million volumes in Polish libraries during World War II, some 100 million in the Soviet Union, and Germany losing at least a third of its own in turn.

The burning of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses in Bradford in January 1989, and the ensuing fatwa that sent the author into years of hiding, was perhaps the most famous recent example of book burning in the Western world. Aside from a few isolated incidents, like the burning of Harry Potter novels by religious activists, or the destruction of Timbuktu libraries by Islamist rebels in 2013, the main avenue for book censorship today are challenges and bans.

According to the American Library Association, the most common causes of challenges are sexually explicit content, offensive language and unsuitability for a certain age group. The first obscenity law was introduced in the United States in 1842 to prevent import of “indecent pictures,” and has since been used to take authors like James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, J.D. Salinger, Allen Ginsberg, Toni Morrison and numerous others — including Merriam Webster’s English Dictionary — off the library shelves across the country.

In 2013, the anti-censorship charity Kids’ Right to Read Project documented a 53% increase in bans from 2012, citing 49 cases in 26 states, with Dev Pilkey’s Captain Underpants coming in at first place, ahead of a far more likely candidate: E.L. James’ Fifty Shades of Grey, ranked fourth. Iran’s new regime has recently promised to relax its stringent censorship laws, while in Britain, a recent ban prohibits inmates from receiving books and magazines from family and friends outside.

Why is Burning and Banning Books Relevant?

The importance of the issues surrounding banning books today is that of fundamental freedoms and civil liberties. While in America the First Amendment protects freedom of expression as a basic right, it is nevertheless not enough to prevent ideas being challenged, books banned and Internet sites blocked on the grounds of difference in interpretation. In countries where freedom of expression is not only not a given, but is completely absent from social culture, the ability to access forbidden information becomes a dangerous necessity, made possible today by advances in technology.

Aside from countries like China and North Korea, where Internet freedoms are curtailed, the samizdat phenomenon of the 20th century is replicated online, giving banned writers a global outlet, and an invaluable resource to readers. What began with the destruction of the Library of Alexandria has now taken on a completely different shape and form. Yet in equating Internet censorship today with book burnings of the past, it becomes a testament to the straight arrow of human curiosity, independent-mindedness and creativity that continues to shape our society through the ages.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.