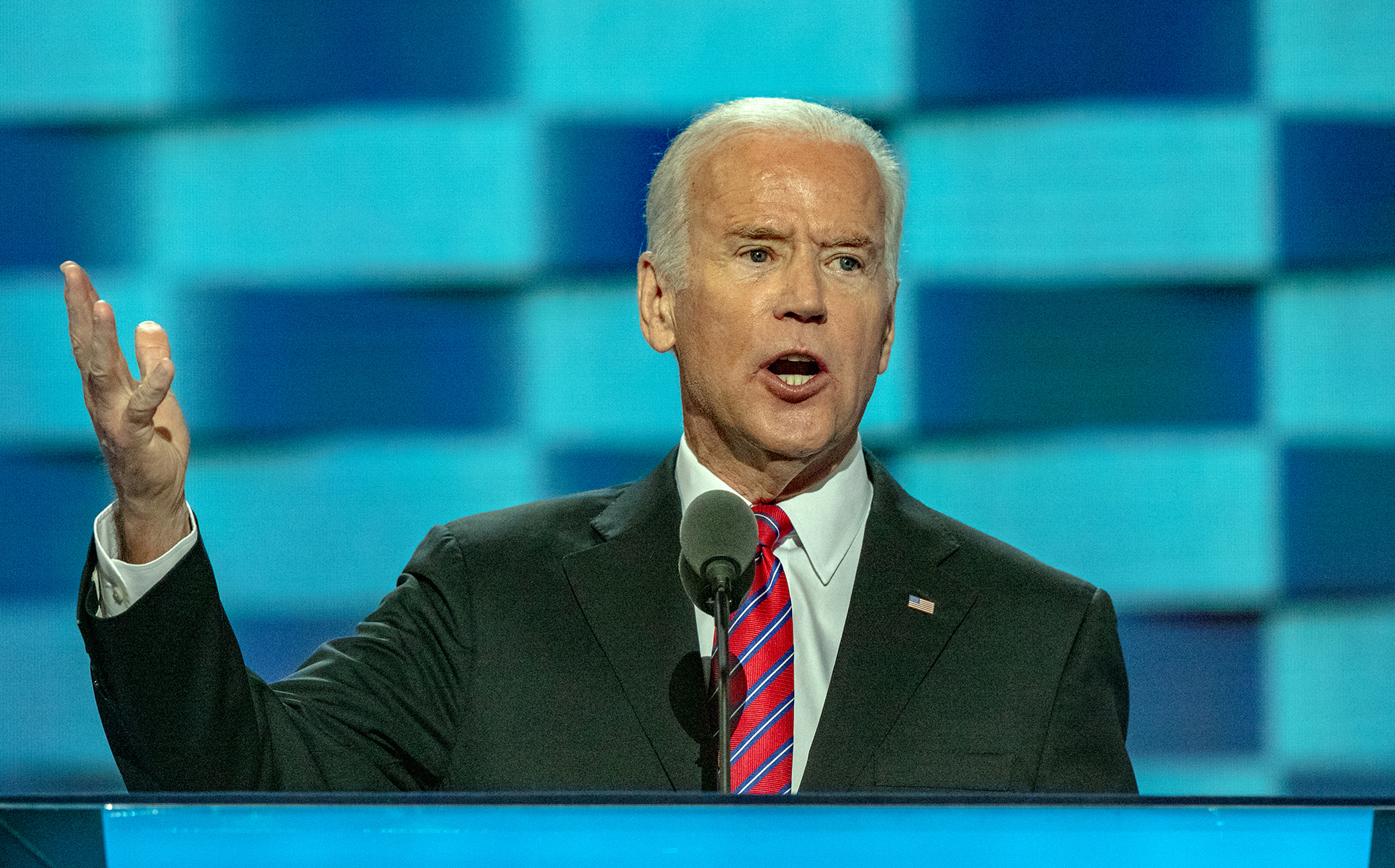

US President Joe Biden positions the Ukraine war as a battle between autocracy and democracy. That reduces what is at stake in the war. The stakes constitute a fundamental building block of a new 21st-century world order: the nature of the state.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine represents the sharp end of the rise of a critical mass of world leaders who think in civilizational rather than national terms. They imagine the ideational and/or physical boundaries of their countries as defined by history, ethnicity, culture, and/or religion rather than international law.

Often that assertion involves denial of the existence of the other and authoritarian or autocratic rule. As a result, Russian President Vladimir Putin is in good company when he justifies his invasion of Ukraine by asserting that Russians and Ukrainians are one people. In other words, Ukrainians as a nation do not exist.

Neither do the Taiwanese or maritime rights of other littoral states in the South China Sea in the mind of Chinese President Xi Jinping. Or Palestinians in the vision of Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu’s coalition partners. Superiority and exceptionalism are guiding principles for men like Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan, India’s Narendra Modi, Hungary’s Victor Orban, and Netanyahu.

In 2018, the Knesset, the Israeli parliament, adopted a controversial basic law defining Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people. “Contrary to Israel’s Declaration of Independence, the nation-state law was seen as enshrining Jewish superiority and Arab inferiority, as bolstering Israel’s Jewish character at the expense of its democratic character, ” said journalist Carolina Landsmann.

Israeli religious Zionist writer Ehud Neor argued that “Israel is not a nation-state in Western terms. It’s a fulfillment of Biblical prophecy that Jewish people were always meant to be in the Holy Land and to follow the Holy Torah, and by doing so, they would be a light unto the world. There is a global mission to Judaism.”

Similarly, Erdogan describes Turkey as “dünyanın vicdanı,” the world’s conscience, a notion that frames his projection of international cooperation and development assistance. “Turkey is presented as a generous patriarch following in the steps of (a particularly benevolent reading of) the Ottoman empire, taking care of those in need—including, importantly, those who have allegedly been forgotten by others. In explicit contrast to Western practices described as self-serving, Turkish altruism comes with the civilizational frame of Muslim charity and solidarity reminiscent of Ottoman grandeur,” said scholars Sebastian Haug and Supriya Roychoudhury.

In an academic comparison, Haug and Roychoudhury compare Erdogan’s notion of Turkish exceptionalism with Modi’s concept of “vishwaguru.” The concept builds on the philosophy of 19th-century Hindu leader Swami Vivekananda. “His rendition of Hinduism, like Gandhian Hindu syncretic thought, ostensibly espouses tolerance and pluralism. With this and similar framings, the adoption of an allegedly Gandhi-inspired syncretic Hindu discourse enables Modi to distance himself politically from the secularist civilizational discourse of (Indian nationalist leader Jawaharlal) Nehru,” the two scholars said. “At the same time, though, Modi’s civilizational discourse, with its indisputable belief in the superiority of Hinduism, has begun to underpin official rhetoric in international forums,” they added.

In a rewrite of history, Putin, in a 5,000-word article published less than a year before the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, portrayed the former Soviet republic as an anti-Russian creation that grounded its legitimacy in erasing “everything that united us” and projecting “the period when Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union as an occupation.”

In doing so, Putin created the justification civilizationalist leaders often apply to either expand or replace the notion of a nation-state defined by hard borders anchored in international law with a more fluid concept of a state with external boundaries demarcated by history, ethnicity, culture, and/or religion, and internal boundaries that differentiate its superior or exceptional civilization from the other.

Civilizationalism serves multiple purposes. Asserting alleged civilizational rights and fending off existential threats help justify authoritarian and autocratic rule.

Dubbed Xivilisation by Global Times, a flagship newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi has redefined civilisation to incorporate autocracy. In March, Xi unveiled his Global Civilization Initiative at a Beijing conference of 500 political parties from 150 countries.

Taking a stab at the Western promotion of democracy and human rights, the initiative suggests that civilisations can live in harmony if they refrain from projecting their values globally. “In other words, ” quipped The Economist, “the West should learn to live with Chinese communism. It may be based on Marxism, a Western theory, but it is also the fruit of China’s ancient culture.” Xi launched his initiative days before Biden co-hosted a virtual Summit for Democracy.

The assertion by a critical mass of world leaders of notions of a civilisational state contrasts starkly with the promotion by Nahdlatul Ulama, the world’s Indonesia-based largest and most moderate Muslim civil society movement, of the nation-state as the replacement in Islamic law of the civilizationalist concept of a caliphate, a unitary state, for the global Muslim community.

Drawing conclusions from their comparison of Erdogan’s Turkey and Modi’s India, Haug and Roychoudhury concluded that civilizationalist claims serve “two distinct but interrelated political projects: attempts to overcome international marginalization and efforts to reinforce authoritarian rule domestically.”

Like Biden, Xi and other civilizationalist leaders are battling for the high ground in a struggle to shape the future world order and its underlying philosophy. Biden’s autocracy vs. democracy paradigm is part of that struggle. But so is the question of whether governance systems are purely political or civilizational. Addressing that question could prove far more decisive for democracies.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.