Timothy Snyder’s latest book is an important addition to the literature explaining where the present crisis of democracy comes from.

A year after On Tyranny, prolific Yale historian Timothy Snyder has written his ninth book, The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America. To call it merely the latest iteration of a new wave of “resistance” literature is to sell it short. Carefully researched in half a dozen languages, the riveting volume is part historical lesson, part political theory and part consolidation of the dizzying political news of the last four years. Two threads weave a vivid tapestry: a narrative with Russia at its center and a more universal political phenomenon that afflicts both Russia and the West.

The historical narrative focuses on Russian President Vladimir Putin who, struggling to develop the economy and decrease stunning inequality at home, chooses to disrupt the European Union and the United States to show that the liberal West provides no alternative to Russia’s inherently superior values. Russia launched the world’s first cyberwar in Estonia in 2007, invaded Ukraine — which President Putin calls an eternal and inalienable part of Russia — in 2014, and initiated subversive political activities in Poland. It provided (and still provides) support for right-wing politicians across Europe, instigated a sophisticated campaign to promote Scotland’s independence and Brexit, and finally provided material assistance to Donald Trump’s election in 2016.

Snyder claims all this is influenced by Russian fascist philosopher Ivan Ilyin who, writing decades earlier, laid the foundation of the Kremlin’s politics of eternal conflict with the West.

The larger thesis focuses on what the author claims the US is experiencing now, and what Russia experienced earlier under Putin — a predictable transfer of the politics of inevitability (where there is no alternative system) to a politics of eternity (where nothing changes and conflicts with the outside are permanent). In this “inevitability” and “eternity” dialectic, Snyder says, political decisions become irrelevant because there are no choices to be made, as was the case with the Washington Consensus in the West and the endless march toward communism in the Soviet Union. As conflicts become eternal, politicians and citizens lose agency and the system degenerates from democracy to authoritarianism — the “road to unfreedom.”

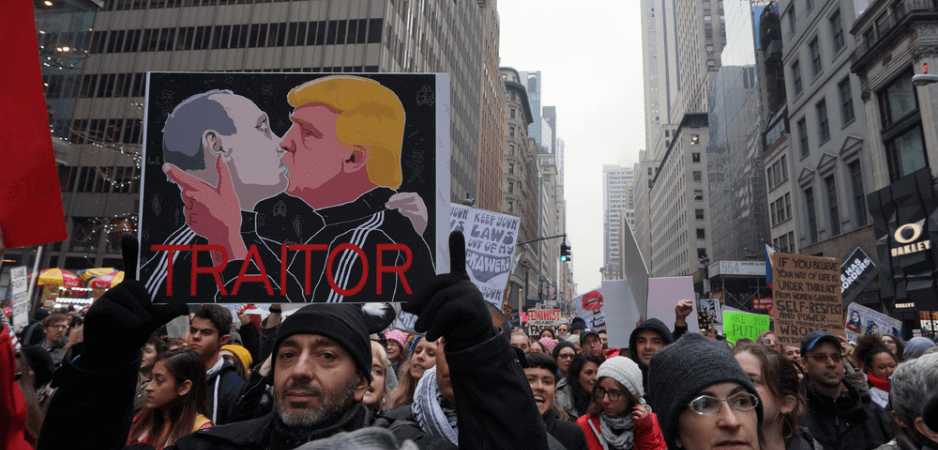

Findings that may surprise readers, even some who follow Russia in earnest, include the intellectual origin of the current regime. Few Western scholars have gone as far as to call Vladimir Putin a fascist (though that is exactly how Snyder refers to Putin and his regime), as the combination of authoritarianism and oligarchy is unique among large countries. Snyder claims that in Putin’s version of fascist politics, a virginal Russia can do no wrong and is under perpetual threat from the decadent, effeminate West. Perhaps the most curious feature Snyder points out is the repeated use of sexual imagery of a masculine Russia at war with a homosexual, atheist Europe and America (deployed especially to distract from other issues).

Even the Western media are not immune to Russian narratives. The author provides clear examples of Russian state media influencing reporting on the Ukraine crisis, resulting in confusion and a delayed EU response, as with Stephen Cohen calling Euromaidan protestors fascists in the popular American publication The Nation. Snyder also contradicts the characterization of the Euromaidan as a coup, arguing: “A coup involves the military or the police or some combination of the two. The Ukrainian military stayed in its barracks,” and that “Even when President Yanukovych fled, no one from the ministries, police, or power ministries sought to take power, as would have been the case during a coup.”

Whether the change in government was a revolution, a coup or something in between, Snyder robustly refutes its characterization as led by fascists, a worrying point of confusion in the West.

Where Is the Bear Suit?

Skeptics may find Russia’s malicious intent convincing, but nonetheless find holes in Snyder’s argument. First, President Trump’s role as Russia’s marionette may seem a robust case, though it relies on a massive accumulation of circumstantial evidence. Over his first two years as president, Donald Trump had warm words for Vladimir Putin, but some claim it is too soon to say definitively that his compliments come from anything more than genuine admiration. As David Brooks has argued: “If you look at the European parties that are populist like Trump, they all are pro-Putin. They just think, I like strongmen. That guy is a strongman, my kind of guy.” On the other hand, the financial support many European rightists enjoy underpins Snyder’s theory.

Though much evidence points toward the same conclusion, there is no “smoking gun,” “no photo of Trump in a bear suit” as the author himself explained in a lecture, and the president is quick to point out that he signed expansions of sanctions against Russia (albeit under pressure from a Republican Senate), increased funding for the European Deterrence Initiative and sent weapons to Ukraine.

The plethora of coincidences and disproportionate number of advisers and cabinet members past and present in the White House with business ties to Russia’s government and oligarchs nonetheless seems too great and too bizarre to ignore. The larger point of Russian government employees and bots fomenting discord in American society has been demonstrated by American intelligence agencies, journalists and the CEOs of Facebook and Twitter. Snyder assembles the facts in a compelling way, and any policymaker unconvinced of the need to take online misinformation seriously will be alarmed by how pervasive and effective Russia’s propaganda machine has been, even among those ostensibly not susceptible to such tactics.

The case of Russia’s manipulation of Polish politics is less convincing. Snyder argues Russian funding has helped sow chaos in the Polish parliament, but if the goal has been to make Warsaw more friendly to Moscow, its failure has been abject. Jarosław Kaczyński, Poland’s de facto ruler, has publicly stated he believes President Putin ordered the murder of his twin brother, then-president Lech Kaczyński, and Polish sentiment toward Russia is at the lowest it has been since the fall of the Soviet Union.

Snyder also paints former Polish Defense Minister Antoni Macierewicz as a compromised official with connections to Russian mobsters. However, Macierewicz’s vociferous assertions that Russia was to blame for the 2010 Smolensk plane crash, which killed President Kaczyński along with Poland’s top military officials and politicians, when he was head of the reopened investigation into the disaster point in the opposite direction. In 2017 Macierewicz claimed Russia plans to invade all of Ukraine and rebuild a Russian empire. Although he has proven a political lightning rod and has caused problems for his party at home and for his country abroad, to call him a Russian traitor is to overstate the case.

Although one can question the wisdom of founding the Territorial Defense Forces (WOT) — a military entity separate from the Polish armed forces hierarchy — The National Interest called the force Warsaw’s “own version of hybrid warfare,” and Felix Chang writes “the WOT’s wartime role will be to counter Russian airborne and special operation forces behind the frontlines.” None of this means Poland is short on problems that have shaken the foundations of its democracy. Controversial reforms to weaken the judiciary have led to a constitutional crisis unlike any seen since 1989. Political polarization and accusations of police overreaction against protestors worry many.

This is not the same as saying Russian influence has done more than cause some opportunistic disruption that has exacerbated existing political problems in the country.

Politics of Responsibility

Although Snyder has painted a compelling picture of the politics of inevitability devolving into the politics of eternity, he does not create as robust a picture of how to fight such perceptions other than a general plea for policies that combat inequality and for politicians to place democracy above party victories and short-term gains. These prescriptions seem more rehashing of a center-left platform and less clearly argued than the rest of the tome.

That is not to say identifying the problem is insufficient. Snyder’s book is an important addition to the literature explaining current events and where the present crisis comes from, and On Tyranny focuses on giving advice for what individuals can do when the signs of tyranny arise — as the author claims it has. For additional specific advice for those fearful for democracy, see How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt.

The book’s great strength is to explain why people think about politics the way they do. The inevitability of capitalism or communism helped make their proponents complacent and vulnerable, and what followed — a politics based on racism, anti-Semitism, permanent conflict against foreigners and “other” world views — is the danger. As long as inequality and oligarchy pervade societies, one can expect more electoral results like Brexit, Donald Trump and an endless Putin regime in the future.

The road to unfreedom is shorter and straighter than anyone could have imagined, and it is the responsibility of all to bring democracy back from the edge of authoritarianism. This is Tim Snyder’s plea. Proponents of liberal democracy avoid it at their peril.

*[The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America is published by Penguin Random House, 2018.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.