Who is likely to lead a ground offensive in Yemen?

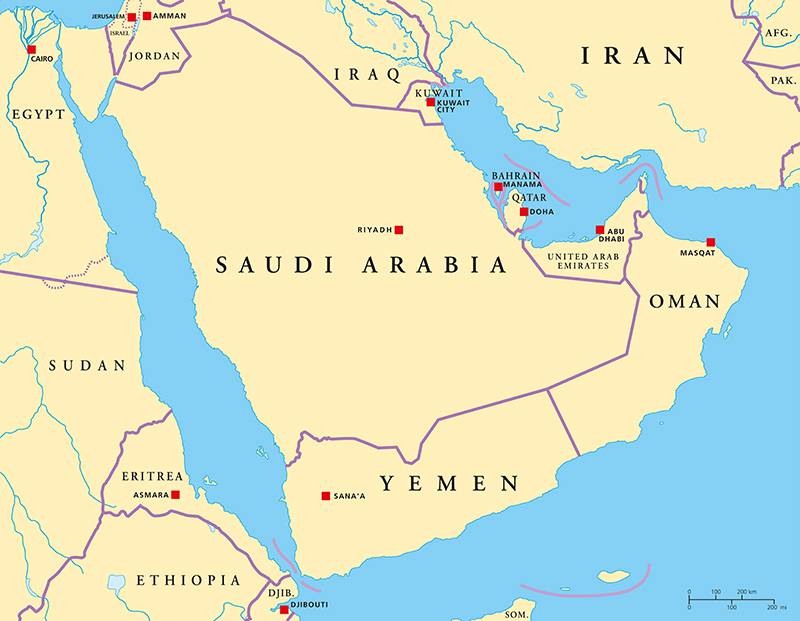

Despite Saudi Arabia declaring an end to Operation Decisive Storm, victory still seems elusive for either side in Yemen as the Saudi-led coalition continues to bomb targets and exerts efforts to coordinate local ground forces. The air campaign has eliminated a number of Houthi and high value military targets, but it has come at a cost in civilian casualties, mainly in the Yemeni capital, Sana’a.

Amid talk of a ceasefire and new dialogue, as Saudi Arabia announced Operation Renewal of Hope on April 21, Houthi leaders remain resilient as militias hold ground in Sana’a and besiege the southern port city of Aden and Taiz in central Yemen. Recent developments point to a protracted ground war to be led by a number of military and tribal leaders loyal to Yemeni President Abdo Rabbo Mansour Hadi against the Houthis and those loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh.

In the political arena, President Hadi, who remains in Riyadh after fleeing Yemen earlier this year, appointed former Prime Minister Khaled Mahfoudh Bahah as his new vice-president to ensure continuity of the government in exile. With assistance from Saudi Arabia, providing weapons and munitions to pro-Hadi militias since the start of the military campaign in March, financial support has led to a number of military and tribal leaders across Yemen’s southern provinces joining the fight on the president’s side.

But a defiant speech by Houthi rebel leader Abdulmalek al-Houthi on April 19 underscored the Saudi-led coalition’s mounting challenges. Ongoing airstrikes causing civilian casualties, and gains made by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in eastern Yemen, simply fuel the Houthis’ resolve to remain on the offensive. In his speech, al-Houthi called upon Yemenis to remain steadfast against the Saudi aggression, and he warned parties and individuals of dire consequences for supporting foreign intervention.

Former President Saleh and his party, the General People’s Congress (GPC), have responded to mounting international pressure by reaching out to neighboring Gulf states in order to start a new round of talks. In a speech after al-Houthi’s televised address, Saleh agreed to work toward a ceasefire as recommended by United Nations Security Council Resolution 2216 of April 14. His words caused an instant reaction from the Houthi camp, threatening to abandon their fragile alliance with the deposed president.

A Fight Over Legitimacy

Every side involved in the ongoing conflict has created its own narrative of legitimacy: Houthis regard themselves as the legitimate representatives of the popular revolution in 2011; southern factions claim a legitimate right to self-determination; deposed President Saleh claims the legitimacy of constitutional continuity; the Sunni Islamist party al-Islah and its allies claim legitimacy through popular support against Saleh’s 33-year rule; President Hadi clings onto legitimacy through having been elected in a one-man election; while Saudi Arabia claims a right to restore order at its southern flank under the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) agreement of 2011.

Saudi Arabia’s primary concern has been to prevent a protracted civil war in Yemen that could spill across its southern border. Many critics have claimed Operation Decisive Storm actually hastened this scenario, which local observers felt was preventable through ongoing UN-mediated talks between all political parties, which had stalled rather than collapsed. Saudi Arabia’s newly appointed foreign minister and former ambassador in Washington, Adel al-Jabeir, claimed the kingdom “would do anything necessary [to restore] the legitimate government in Yemen,” meaning President Hadi.

A top objective for the military campaign was to restore order and force the “Iranian proxy” to abandon all government institutions and give up its weapons. The order of concern to Yemen’s northern neighbor and long-time financial supporter is rooted in the 2011 GCC agreement and the stability required to prevent dissent within its own borders. The six Gulf monarchies composing the GCC were not about to allow a Shiite-aligned militia to inspire revolt within fragile societies in a post-Arab Spring era.

Shaping Yemen’s Future?

A more difficult task, the Saudi-led military campaign aims to reestablish Saudi Arabia’s ability to shape Yemen’s future. Saudi ties to a whole range of actors in Yemen reach back decades. But the breakdown of order in 2011 damaged Saudi Arabia’s relations with Yemeni political and tribal actors. The uprising ignited a conflict Saudi Arabia had worked arduously to prevent since 1967.

At the end of the revolution against the last Zaydi imam — who Saudi Arabia supported — in northern Yemen, Saudi Arabia established itself as the patron of numerous military, political and tribal leaders, a role later re-enforced following the short civil war between north and south in 1994.

The order created under the ruling triumvirate of Ali Abdullah Saleh, Gen. Ali Muhsin and prominent Shaykh Abdullah bin Hussein al-Ahmar broke in March 2011 when Muhsin joined the uprising sponsored by Hamid bin Abdullah al-Ahmar. Relations between the three camps had already begun to strain following the death of Shaykh Abdullah in 2007 and were exacerbated by Saleh’s alleged attempt to eliminate Muhsin in order to install his eldest son, Ahmed Ali Saleh, as his successor. The 2011 uprising weakened Saleh politically and hurt his relations with Saudi Arabia, the sponsor of the GCC agreement replacing him.

Furthermore, while Muhsin and Shaykh Abdullah’s clan jockeyed for control of the state under Hadi, the Houthi rebels delivered a historic death blow to the Ahmar family and their military and tribal allies in Amran in July 2014, and then moved against the latter’s political ally, al-Islah, later in September.

Saudi Arabia appears to fear the rise of a new order in Yemen challenging its position as the hegemon in the Arabian Peninsula. The kingdom was not completely comfortable with the outcome of Yemen’s nine-month long National Dialogue Conference, in particular the proposal to establish a six-region federal system. The emergence of unfamiliar new centers of power, especially following the breakup of the Bakil and Hashid tribal confederations in northern Yemen, laid the foundations for an unpredictable future along Saudi Arabia’s southern flank.

Hashid tribes, controlled by the Ahmar family throughout the 20th century, were pillars of the republican regime. After the conflict in Amran — Ahmar territory — tribal members like Khalid Ahmed al-Radhi say: “Hashid is no longer the same as [we knew] it, one solid tribe following one leader … Hashid was divided in 2011, [and it] will be that way until someone steps up and takes the lead.”

Bakil, which lacked Hashid’s cohesion under Ahmar, is also divided among Saleh’s supporters, allies of the Islah party and some supporting the Houthi rebels. This fracturing of the established order, particularly in north Yemen, worries Saudi Arabia as the battle over control of the state may bring years of instability at the kingdom’s doorstep.

The Ground Offensive: Who’s Who?

The Saudi-led military campaign planned for a ground assault following an extensive air campaign. Saudi Arabia believed allies like Egypt, Pakistan and Sudan would supply troops for an incursion to secure physical territory in Yemen. In an unexpected turn of events, two weeks into Operation Decisive Storm, Pakistan’s parliament issued a resolution preventing the government from sending troops into Yemen. Such developments led to a change in strategy, increasing delivery of weapons and money to elements in south Yemen pledging to fight Houthi rebels.

Adding to new challenges faced by the Saudi-led coalition is the fact President Hadi already lacked significant support among military officers prior to leaving for Saudi Arabia. Othman BaBoukhan, a London-based southern activist, told this author: “Hadi completely lost any influence over any trained army [units] to take back Aden” from Houthi rebels.

Lacking an exit strategy, and refusing to engage in talks until Houthis lay down their weapons, hopes now rest on Commander Thabet Muthana Jawas from the southern Lahj governorate bordering Aden, who leads a small unit trying to take back al-Anad air base located in the governorate. Jawas was initially rejected as commander of the Special Security Forces (SSF) in Aden by the Houthis, accusing him of being one of those responsible for killing Hussein al-Houthi, the founder of the Zaydi-Shiite rebel group, in 2004.

Thabet Jawas, Gen. Abdulrahaman al-Halili and individuals like Saleh bin Farid and Awadh al-Thawsli in Shebwa province represent Hadi’s primary ground forces, along with elements of the Hadhramawt Tribal Confederacy (HTC). Tribal elements in central Mareb province are far from pledging allegiance to Hadi, but they are suspected of receiving aid coordinated from Riyadh.

Some tribal camps in Mareb have been pictured displaying Saudi Arabia’s flag on tents and vehicles. But Jawas, Halili and the HTC are highly fragmented elements tasked with recruiting men to fight Houthis on the ground. By dropping weapons, munitions, communications equipment and cash, Saudi Arabia hopes to encourage elements to pledge allegiance to Hadi and facilitate coordination between groups across southern provinces, from Aden to Shebwa and Hadhramawt. The problem, as media outlets have reported, is that Saudi Arabia lacks a plan to secure Hadi’s legitimacy and that of his office, meaning continuity of the transition process.

A recent Reuters report, citing an official Yemeni source, said that 300 tribal fighters were trained in Saudi Arabia and then sent back to their home area in the Sirwah district of Mareb province. The same report also noted that heads of tribes were invited to a meeting in Riyadh in an effort to build a united front against the Houthis.

Saudi Arabia’s efforts to shape the conflict on the ground, by mainly dropping military supplies and cash, are having mixed results. Houthi rebels have been quick to post pictures of Saudi weapons captured nearly after every drop in the area of Aden. Others post pictures of weapons with Saudi Arabia’s logos being sold in the black market. Aside from logistical errors, the air drops, particularly in Aden, have played a major role in shaping the conflict. Adenis, previously dedicated to a peaceful revolution and simply employing civil disobedience to protest Sana’a’s grip, have now prevented the Houthi militia from taking full control of the province with weapons provided by Saudi Arabia.

With the announcement of Operation Renewal of Hope, a second phase said to involve talks about a political solution as well as troop mobilization at the Saudi-Yemen border, observers remain concerned over the nature of the coming ground operation. Concerns over the start of a ground offensive have increased, even as an initiative proposed by the Sultanate of Oman aims to de-escalate the conflict and restart talks. The urgency to restart peace talks was also highlighted by Omani diplomat Abdullah al-Ba’dy, who was quoted during an event hosted by the Arab Center as saying the conflict of today may produce a Yemen beyond control.

The fear of a protracted catastrophe among a number of observers in Sana’a is that the Saudi-led coalition is empowering local actors that will challenge central authority for years to come. This also reflects the observation that Saudi Arabia is unlikely to be able to launch its own independent ground offensive. Members of the southern secessionist movement have yet to pledge support for Hadi as the legitimate president, especially since he continues to support Yemen’s unity, which southerners reject outright.

Each side merely sees the other as an instrument of resistance against Houthis. At the moment, military and tribal leaders have one target: defeating the Houthi militias. But the big question is: How will this translate into support for Hadi’s return? In a protracted armed conflict with Houthis these military officers and tribal leaders may simply become a type of proconsul, well-funded and armed regional administrators of battle-fronts for Saudi Arabia, in the absence of an organized ground offensive that brings about an end to hostilities.

Such a move would expand the authority and security vacuum across Yemen. The window of opportunity to avert this scenario is small, but it still exists. Only a comprehensive dialogue can empower the role of state institutions and restore legitimacy to central authority.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Sunsinger / Peter Hermes Furian / Anton_Ivanov / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.