Commentary on Egypt’s roster of candidates for the upcoming presidential elections.

Finally, the moment we have all been waiting for. Nearly a year and a half after a popular revolution that accomplished the once unfathomable and toppled the brutish dictatorship of Hosni Mubarak, the time has come to witness the next leap forward in Egypt’s quest for democracy. The first round of polling on May 23 and 24 will mark the first free and fair presidential elections in Egypt’s history.

As Egyptians ponder over whom they will choose to lead their country through the aftermath of a tumultuous revolution, the question at the back of many observers’ minds lingers: what form will the county take when the next president presses his agenda? Will he be successful in prying power away from the military and to a civilian authority?

With presidential candidates running the ideological gamut, Egyptians and outside observers anxiously wait to see whether Egypt will follow the currents of resurgent Islamism to assume the form of a conservative theocracy, revert to Nasserist socialism, blossom into a liberal civil state, or return to a Mubarak-esque state of political dystopia.

Amongst the cornucopia of candidates, five frontrunners have emerged. What follows is an attempt to simplify this diverse political portrait.

Amr Moussa

A long-time statesman, accomplished diplomat, and self-proclaimed liberal, Amr Moussa served as foreign minister to former President Mubarak from 1991 to 2001. He was then the secretary-general of the Arab League from 2001 until 2011.

Earlier in his career, Moussa served as Egypt’s permanent representative to the United Nations and worked in several Egyptian missions in foreign countries, namely the US and Switzerland. Under Mubarak, Moussa forged good personal relationships with many Arab leaders — especially in the Gulf — while gaining popularity in Egypt for his harsh criticisms of Israeli policies and for his vocal support for Palestinians during the second Intifada.

During the revolution, he voiced cautious support for the popular uprising but never directly called for Mubarak to step down. In fact, during an interview he stated that he would vote for Mubarak if he ran for a sixth term (he later clarified that this was his alternative to voting for Gamal, Mubarak’s son who was being groomed as his successor) — nonetheless, this is surely held against him by anti-regime activists.

Moussa has managed to garner significant support among secular liberals, Copts, as well as supporters of the old regime who find comfort in his commitment to a civil (as opposed to Islamic) state and his progressive political agenda. His close association with the old regime leads many revolutionary youths to shun his candidacy and dub him a felool — a derogatory term used to insult remnants of Mubarak’s regime.

However, the fact that he was removed from the foreign ministry at the height of his popularity makes many believe that Mubarak perceived him as a potential political threat. This explanation, his supporters argue, sufficiently distances him from the previous regime. Moussa’s supporters argue that his charisma grouped with his political savvy and diplomatic experience makes him best suited to mitigate the challenges of the post-revolution era. His familiarity with the old regime may prove useful in negotiating power away from the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) and into a civilian authority. Critics say that at 75, his age gives him an inherently “old school” mentality incapable of adapting to the aspirations of youthful revolutionaries.

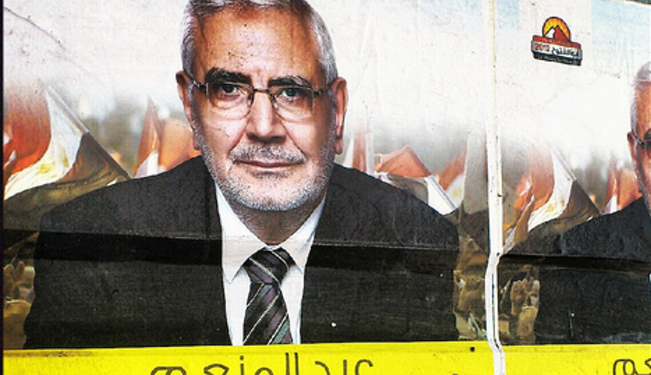

Abdel Moneim Abol-Fotouh

Educated as both a physician and a lawyer, Abdel Moneim Abol-Fotouh led a politically active life since his university years. Abol-Fotouh made his first mark on the political scene whilst president of Cairo University’s student union in the 1970s. During a speech by former president Anwar el Sadat, he famously stood up and criticized the president to his face, censuring him for his repression of Islamic political activity and peaceful demonstrations. Sadat eventually jailed him along with 1500 other politically active intellectuals during a widespread crackdown against regime dissent. Abol-Fotouh was imprisoned again twice under Mubarak for allegedly conspiring to bring down the regime.

Despite repression from the regime, political Islam was trending in Egypt’s universities, and Abol-Fotouh actively participated in the grassroots social welfare and educational efforts of the underground “parallel” Islamic sector that flourished outside of government control during this time. Abol-Fotouh worked closely with the Muslim Brotherhood for many years, and rose to its highest executive office in a position he held from 1987 until he left in 2009.

He was officially dismissed from the organization in the summer of 2011 following his bid for presidency after the Brotherhood had stated it would not field a candidate (a position which it later reneged). Some observers believe his departure from the Brotherhood marked an internal purge within the organization: Abol-Fotouh, who was once markedly conservative in his Islamism, became a reformist and embraced a leftward shift in ideology, particularly regarding social issues. He maintains that he left the organization because the Muslim Brotherhood’s founders never wanted it to become a political party, wanting it to focus instead on social and religious advocacy.

A long time opponent of the old regime, Abol-Fotouh championed the January 25 revolution and actively participated in demonstrations from the very start; he was admired for setting up field hospitals for wounded protesters in Tahrir square.

His positions on religious and gender equality have gained him the support of many liberals, while his Islamist past appeals to conservatives who place a great deal of emphasis on religion. It is Abol-Fotouh’s Islamist and progressive dichotomy that gives him a broad appeal across Egyptian society unmatched by any other presidential candidate. Even before the revolution, his prominent role in the pro-democracy Kefaya (enough) movement mobilized liberals and Islamists alike in demanding democratic reforms from the Mubarak government.

With the plurality of visions for Egypt’s second republic that exists today, supporters believe that his broad appeal and populist agenda can potentially bring unity to Egypt, something that has remained elusive since the revolution. But Abol-Fotouh’s liberal critics fear that once he is elected, he will abandon his promises of moderation, and assist the Islamist-majority parliament to edge Egypt into a full-fledged theocracy — a sort of “stealth Islamization” of Egyptian society. On the other hand, critics on the far-right criticize Abol-Fotouh for being too liberal in his Islamism, especially on social issues. For instance, he has stated that he would consider appointing a female or Christian vice president.

Mohammad Morsi

Mohammad Morsi is president of the Muslim Brotherhood’s official political wing, the Freedom and Justice Party. An engineer by training, Morsi earned a bachelor’s degree in Cairo before receiving his master’s and PhD in rocket science at the University of Southern California.

After working in academia for several years both in the US and Egypt, Morsi joined the Muslim Brotherhood’s religious department and rose steadily through its ranks, finally becoming a member of its highest cabal, the Guidance Bureau. When Mubarak eased restrictions on unofficial political activity by Islamists in the mid-nineties, Morsi ran for Egypt’s lower legislative house as an independent and served as the spokesperson for the Brotherhood’s independent parliamentary bloc. He was re-elected in 2000, and in his capacity as a parliamentarian and Muslim Brotherhood leader, advocated for democratic reform, most notably as a co-founder of the Kefaya movement.

Morsi was not in Cairo at the start of the January 25 revolution, but his prominence within the Muslim Brotherhood led to his arrest in the Western Desert by Mubarak’s security forces. However, the Muslim Brotherhood, which has maintained a highly capable volunteer network since the 1970s, was a key mobilizing force against the Mubarak regime during the revolution. This efficient organizational mechanism is Morsi’s main advantage in the election, as the Brotherhood will unleash its hoards of volunteers to mobilize potential supporters and garner votes, especially in Egypt’s poorer and rural areas.

Throughout the presidential campaign, miles of Cairo’s streets could be seen lined with Muslim Brotherhood volunteers holding Mohammad Morsi placards. Ideologically, Morsi caters to the Egyptian religious right, and openly advocates for the integration of Islamic Shari’a law into Egypt’s legal apparatus. If elected, he benefits from having a Muslim Brotherhood dominated parliament with an Islamist majority to carry out his conservative Islamist agenda. Some Christians and secular liberals have vowed to leave Egypt if he is elected.

Hamdeen Sabahi

Founder of the Nasserist Al-Karama Party, Hamdeen Sabahi vows a return to a dignified, independent Egypt. Sabahi was born into a modest background of peasants and fishermen on Egypt’s north coast. He made his way into Cairo University where he studied mass communication and served as editor-in-chief of the university’s student-run magazine, as well as the head of the student union. A politically active student, Sabahi established a pro-Nasser organization aimed at opposing President Sadat’s engagement with the West and peace with Israel.

He was jailed in a crackdown against opposition in 1981 along with 1500 other political activists and intellectuals (the same sweep that captured fellow candidate Abol-Fotouh). Sabahi was jailed again under Mubarak’s regime for allegedly inciting protest by agricultural laborers against legislation that benefitted landowners over farmers.

Later, after parting ways with the Arab Democratic Nasserist party due to internal strife, he founded the Al-Karama party and ran twice for parliament under its banner in 2000 and 2005. He was jailed for a second time under Mubarak for organizing anti-US demonstrations opposing the Iraq war. Sabahi co-founded pro-democratization movements that emerged in Egypt throughout the 2000s, most notably the Kefaya movement and the National Assembly for Change that sought constitutional reform and social justice.

Sabahi took an active role during the January 25 revolution, protesting in Tahrir Square and mobilizing opposition to the old regime in his home government on the north coast. After Mubarak’s ouster, he has remained an outspoken critic of the military regime that is still in power, and has participated in a number of anti-military demonstrations since then. He believes the SCAF should be held accountable for the abuses it committed during the transitional period.

In adherence with his leftist, Nasserist platform, Sabahi aims to significantly increase the role of the public sector in the economy. He contends that the prolific privatization that took place under Mubarak was extremely corrupt, and wants to re-absorb many of these private entities into the state. He pledges a hard line against Western, specifically American, intervention in Egyptian domestic politics, and views Israel as a national threat to Egypt.

Opponents fear that these positions will alienate Egyptians on an international level, and end the American domestic and military aid that many in Egypt rely on. Other critics fear the ruthless political repression that was a namesake of former President Nasser’s regime. Some liberals worry that Sabahi’s leftist appeal will draw votes away from Abol-Fotouh and Moussa, leading to the worst case scenario for liberals: a runoff between Morsi and Ahmad Shafiq.

Ahmad Shafiq

An old regime stalwart, Ahmad Shafiq was the last prime minister appointed by Mubarak in his unsuccessful last-ditch effort to appease protesters during the popular uprising that removed him from office.

Shafiq’s career began in the military, where he graduated from the Egyptian Air Force Academy. A fighter pilot during the 1973 war against Israel, he served directly under Mubarak, who was the commander of the Egyptian Air Force until he was picked to be Sadat’s vice president. Shafiq rose steadily through Air Force ranks, becoming Air Force chief of staff and eventually reaching Mubarak’s former role as Air Force Commander. Mubarak then appointed Shafiq as his aviation minister in 2002, a position he served until the January 25 revolution.

Shafiq’s support comes primarily from those in Egyptian society who supported the ousted president and fear change to the status quo. Egyptians disillusioned by the lawlessness and political violence that have followed the revolution, feel that reverting to a member of the old regime will bring back stability. His supporters among the Egyptian high-rolling “ex-elite” hope he will continue Mubarak’s business-friendly economic policies that lined their pockets during his reign.

Many Coptic Christians support Shafiq, because their worst fear is an Islamist takeover of Egypt and a shift to an Islamic theocracy. In their view, a remnant of the old regime that suppressed Islamists for so long will prevent this from happening.

His critics call him the worst of the felool and insist that a vote for Shafiq is like a vote for Mubarak.

Shafiq’s candidacy cannot be disregarded because he is the candidate of the military establishment — the SCAF — which is still in power.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.