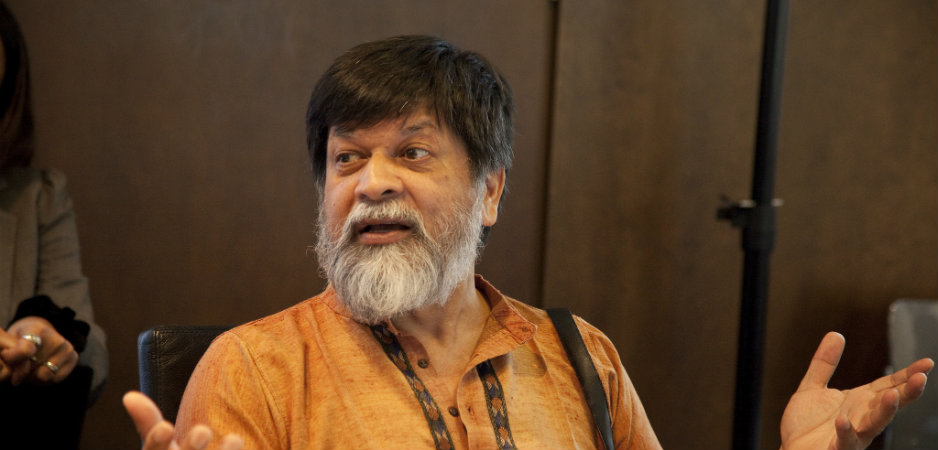

In this edition of The Interview, Fair Observer talks to the renowned Bangladeshi photographer and activist Shahidul Alam.

At a time when censorship is growing across the globe, Shahidul Alam — a renowned Bangladeshi photographer and social activist — has pledged his life to represent the downtrodden and insists that he “will remain a thorn for the oppressor.” Over the years, Alam’s work has concerned itself with the representation of political violence and social change.

Having first obtained a PhD in chemistry from the University of London, Alam returned to Dhaka to focus on photography, setting up the award-winning Drik Picture Library in 1989. His work depicts everyday life in Bangladesh, following the lives of sex workers and women who joined the Naxalite movement to fight against oppression, telling the story of the Rohingya refugees and showing the resilience of marginalized indigenous people and survivors of natural disasters. What becomes immediately obvious from his work is a deep concern for the lives of working people. Alam’s powerful depictions of lives of migrant laborers and those engaged in the informal sector explain his belief in recognizing the role they need to play in improving governance in Bangladesh.

In August 2018, Alam was detained following an interview with Al Jazeera in which he criticized the government’s use of violence against students protesting road safety in Bangladesh. Held under the controversial Information and Communication Technology Act for more than 100 days, Alam’s imprisonment garnered a wave of support from around the world, putting pressure on Sheikh Hasina’s government. Now out on bail, Alam continues to face charges that can mean up to 14 years in prison.

In this edition of The Interview, Fair Observer talks to Shahidul Alam about the current political climate in Bangladesh, his work as a photographer in a censored environment as well as his sense of duty toward his homeland.

Anna Pivovarchuk: First of all, from all of us at Fair Observer, we want to express our relief at your release from jail. We are very glad to see you well and free. Your arrest in August 2018 has garnered enormous support from around the world. Were you aware of the numerous campaign efforts fighting for your freedom?

Shahidul Alam: I am not free. The case against me still stands. I am merely out on bail. If sentenced, I potentially face up to 14 years in jail. So the pressure to drop the case needs to continue. On the other hand, if one cannot freely express one’s opinion, if dissent is quashed, if it is impossible to question authority, then no one in Bangladesh is free.

There were several stages to my detention. In the first phase, immediately after I was abducted and tortured, I had no idea of how much others knew. I had tried screaming out to people, but didn’t know if others knew either where I was, or if I was alive. I managed to see the TV when I was being taken to the police headquarters the following morning, and saw that information of my arrest was on the newsfeed. I didn’t know what was happening outside, but was confident my friends and the global community would be supporting me.

While in jail, other inmates told me of the statement by Nobel laureates. In the first jail visit, Rahnuma [Ahmed, Alam’s partner] and Saydia [Gulrukh, journalist and director at Drik agency] told me about the letter by Raghu Rai, and later I also learnt of the statement by Arundhati Roy, Noam Chomsky and others. I didn’t have detailed information, but knew by then it was a massive campaign.

Pivovarchuk: What was the hardest part of your detention?

Alam: Accepting the fact that I could not play an active part in the resistance. I knew the country was in trouble, and I had a role to play. There was much more work to be done, and I felt I wasn’t doing my share. At the jail visits, I tried to tell my friends to concentrate less on me and more on the movement. The second hardest was hearing the stories of my fellow prisoners. Many inmates came to tell me their stories — stories of injustice and pain which tormented me, especially as there was little I could do besides being a sounding board.

Pivovarchuk: Indeed, Bangladesh’s social and political milieu has been growing increasingly violent and intolerant of dissent, with brutal and often deadly attacks against free thinkers. You have strong connections to the UK, where you hold residency, yet you chose to live and work in your homeland. What prompted this return to Bangladesh, given the difficult conditions when it comes to freedom of speech and expression?

Alam: I was studying and teaching in the UK. Even as a student, I worked and earned money. I was given residency in the UK by virtue of having been a taxpayer for many years. I never applied for it. I am a Bangladeshi citizen and my allegiance is to my people. I also consider myself to be a global citizen, and global issues do concern me, but Bangladesh has given me far more than I’ll ever be able to give back. Yes, there are difficulties, but as a privileged Bangladeshi, the onus is upon me and others like me to do what we can to right these wrongs. I can hardly expect someone else to fix my country.

Nilanjana Sen: Do you see similar trends with regard to censorship of critical voices occurring worldwide? Or does something set the South Asian context apart, and Bangladesh in particular?

Alam: Levels differ widely, but I do not know of a single nation that does not champion freedom and democracy in its rhetoric but actively opposes it in its practice. Bangladesh and South Asia are at the wrong end of this spectrum, Scandinavian countries being at the other end. But as long as the military-industrial complex plays such an important role in the world economy, critical voices will be suppressed. Besides, powerful nations find it much more expedient to work with pliant dictators than with messy democracies. As long as our autocracies satisfy major corporate interests, as long as they do the dirty work of powerful nations, they will be supported. It is the same across the globe. Morality has little to do with global politics.

Sen: As a photographer, given the constraints under which you often work, what are the kind of compromises you have to make? What are the challenges when you work in a censored environment? And are there any surprising advantages?

Alam: There are times when one takes advantage of people’s vanity or allows the powerful to fall into their own traps. I am aware that I have not always made full disclosure when avoidance has been an option. I have also been deceptive when my survival has depended on it. In an ideal world one would not have to resort to such tactics, but when one considers the greater public good, some compromises need to be made. That people are so susceptible to their own conceit is surprising. When people surround themselves with sycophants, they leave big chinks in their armor. Arrogance leads to vulnerabilities, which can be exploited.

Alam: There are times when one takes advantage of people’s vanity or allows the powerful to fall into their own traps. I am aware that I have not always made full disclosure when avoidance has been an option. I have also been deceptive when my survival has depended on it. In an ideal world one would not have to resort to such tactics, but when one considers the greater public good, some compromises need to be made. That people are so susceptible to their own conceit is surprising. When people surround themselves with sycophants, they leave big chinks in their armor. Arrogance leads to vulnerabilities, which can be exploited.

Sen: Your work is concerned with representation of political violence and social change. You probe the roots of censorship, capture images of marginalization, giving your subjects a voice — all of which has given you an activist label. As you capture the spirit of the time and the historic moments in Bangladesh, do you think you can do this objectively? And what does objectivity even mean when it comes to human suffering, like we see with the Rohingya refugees, for example?

Alam: In an unequal world, staying on the fence means supporting the status quo. I do take sides and am clearly on the side of the oppressed. But I wear my allegiance on my sleeve. I take pains to ensure I am not being unfair, or am not distorting facts or misrepresenting the story, but yes, I take positions, whether it be Rohingya refugees or downtrodden peasants. I will remain a thorn for the oppressor.

Sen: Do you think photography is a better tool than other art forms to question authority? Is it a medium that can overcome barriers – national, regional, cultural — more easily, perhaps?

Alam: It is precisely because I recognize the power of photography that it is the weapon of my choice, but it is not always the best weapon. There are times when words or dance, or even silence might work better. Often it is a combination that works best. I am not married to photography. I will use it when it works, to maximum effect, and abandon it when it fails. I use the most powerful weapon in my arsenal, and often it is photography.

Pivovarchuk: The recent election, where the ruling Awami League won a disputed, yet a landslide victory, suggests little scope for change at the moment. What are your hopes for Bangladesh in the near future? What needs to happen for change to take root?

Alam: The Awami League knows it rigged the elections. They know their “victory” is hollow. It is a weakness they will constantly need to defend. There is a suppressed anger that is very difficult to contain. Even people who are sympathetic to the Awami League resent that the nation has been robbed. There is a climate of fear, but fear does not buy allegiance. The youth who took to the streets continue to be angry.

What gives me hope is that they still believe. That they have not sold out. There are very committed people working at grassroots levels. They lack resources and are not plugged into networks. With the right guidance and support, they can become drivers of change. The real heroes of Bangladesh are the migrant workers, the garment workers and the millions who work in the informal sector. They are the ones who generate the bulk of Bangladesh’s wealth. If they can gain skills and move up the value chain, and are not exploited in the process, and if they can have a say in the process of governance, Bangladesh can surge ahead.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.