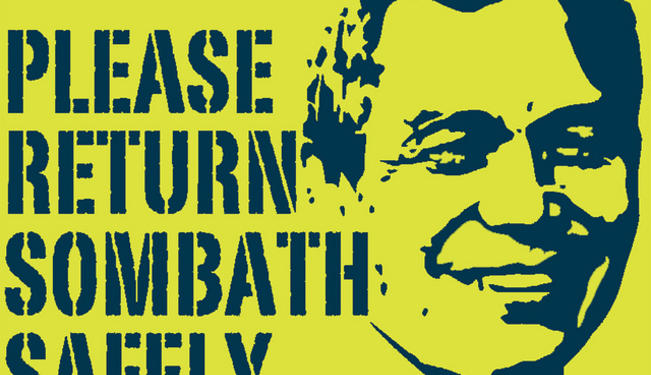

The abduction of the highly respected community leader Sombath Somphone sheds light on the challenges Lao society has to face.

Though usually depicted as a country filled with wild nature populated by people with an outstanding laissez-faire mentality, discourse regarding Laos has shifted these days. A civil society forum infiltrated by state security forces, the expulsion of a foreign NGO director, and the abduction of an award winning community leader, provide the basis for a revival of Western Cold War narratives. The worldwide attention given to these incidences are part of a series of distressing developments in Laos. They shed light on power structures; structures far more complex than clichés suggest.

More than a month has passed since the Magsaysay Award laureate Sombath Somphone disappeared in the streets of Vientiane. Hope for his reappearance seems to have vanished. Shortly after being stopped by traffic police in the capital Vientiane, this elderly gentleman was driven away in a van. The scene, captured by a surveillance camera, was made public on YouTube by Sombath’s family members, who had a chance to view the video material in a police station. Official statements issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs suggest that a business dispute led to the kidnapping of Sombath. Other interpretations of the incident favor a more likely theory, which infers that his engagement with the Lao civil society antagonized powerful people in the fields of business and government. These powerful people may have felt that he had gone too far with his critique of the country’s policies encouraging rapid development.

“Sombath has known and feared the dangers surrounding him for years,” a former co-worker said. He added, “How surreal, that a man who knew the system so well, who was always able to find a way to work with officials and who was so influential could suddenly disappear.” After years of cooperating with the government through his provision of education and advice to farmers, Sombath founded the Participatory Development Training Centre (PADETC) in 1996. He established the PADETC under the Ministry of Education at a time when Lao NGOs were still prohibited by a state which claimed to represent the whole of society. This fruitful venture allowed youth to benefit from a broad education, something of particular importance for Sombath, who encouraged his apprentices to get involved as engaged community leaders. PADETC and its numerous offspring projects continue to work with a multidimensional approach aiming at improvement of people’s livelihoods. Sombath retired from managing PADETC in 2012 in order to refocus his energies on what he saw as a global “crisis in wisdom and human spirituality.”

In his keynote speech for the 9th Asia-Europe People’s Forum (AEPF), held in Vientiane from November 5-9, 2012, he criticized unsustainable growth, which he claims is destroying the earth, unbalancing power relations, and dismantling social coherence. Comprehensive education and Buddhist values, he suggests, offer a way to overcome this modern world of “physical comfort and weakened minds.” Sombath’s conclusive analysis is nothing less than a rethinking of modernity, one which acknowledges the interconnectedness of economy, nature, society, and governance. He encourages individuals to aspire toward balanced development that does not profit one and harms another part of this system. This, he urges, can only be achieved when people, corporations, and government engage in open dialogue of mutual respect – a dialogue that has been suppressed in the past. Participants in the AEPF reported harassment and surveillance – for instance the disappearance of the keynote speech’s hardcopies, making it appear as if nothing was ever said. Obviously, authorities were concerned about what issues may have been addressed at the AEPF and made clear that the Politburo does not yet approve fully the idea of the establishment of an organized civil society.

Albeit, the Lao government’s Decree on Associations in 2009 granted recognition to those civil, non-profit associations (NPA) with state affiliation, many viable NPA’s were not conferred legal recognition. The paternalistic policy of the state encourages potential NPAs to take the first step and apply to become legally registered as NPAs. However, at the same time, the government wants to ensure that these NPAs do not enjoy too much independence. The mere potential of these small associations – to create a platform for debates not in line with the party’s discourse – is feared by the Party. Therefore, counteractive measures tend to be rather extreme. Sombath Somphone’s disappearance is not an anomaly; it is just the tip of the iceberg.

Still, one should not jump to conclusions regarding a governing body whose right hand never knows what the left is doing. Composed of factions with very different interests, the nature of this opaque state of affairs furthers the ambiguity over the identity of the conspirators responsible for Sombath’s abduction and also obfuscates the issues he addressed.

Power structures can be examined at the intersection of state and business where massive foreign investment interests hit a country which can be found at the bottom of the Corruption Perceptions Index list – the 160th rank which is shared with Libya and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This combination means that those authorities in the right position to gain access over the country’s vast natural resources can obtain vast riches. Not all officials are willing to abuse their authority; those still committed to the ideals of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party are numerous, though losing their access to power. Dams, golf courses, hotels, convention centers, shopping malls and plantations – whether in Vientiane or the remotest village – show that the mining sector is not the only one that turns land into gold. While researchers and lawmakers attempt to adequately understand and mitigate the controversies surrounding land investments in Laos, land grabbing continues to be a threat to people’s livelihoods.

The absurd manner in which functionaries try to belittle large issues could be observed at the AEPF. At the conference, officials were showcased as successfully resettled villagers, reciting invented stories of their marvelous lives after the relocation of their homes. These desperate acts belie the often sad reality. The case of Sivanxay Phommarath, for example, provides one testimony of a development approach at the cost of people’s rights. Radio Free Asia reports that the Lao woman has been detained in the Khammouane provincial prison since October 2012, though no charges were made against her. According to the article, Sivanxay and other villagers refused to abandon their land to make way for a road expansion project close to Nam Theun 2, Laos’s largest hydroelectric dam. These villagers tried to seek advice about compensation from an influential consulting group. Even though the meeting with the unknown consulting group never took place, all villagers were taken under custody and questioned about the unknown group they sought to meet. Lao authorities believed that Sivanxay deprived them of information, and therefore detained her for further investigations.

In January 2012, the Lao government took a popular call-in radio show off the air, after it had served as the sole debating platform for sensitive issues, where Lao citizens were able to anonymously report about their concerns. This incident made clear that the economic opening of Laos does not foster democratic values like free speech. Just a few days before Somphone’s disappearance, the government expelled Anne-Sophie Gindroz, the director of a Swiss NGO who was also involved with the AEPF. The expulsion was a reaction to a personal letter that she sent to the country’s development partners, wherein she criticized state repression in Laos. Yet, as stated in the AEPF’s keynote speech, good governance can only be achieved by hearing the voices of the Lao people. The Party, once sovereign over the discourse in the country through a system of censorship, now faces the challenging reality of 21st century global interconnectedness. Modern communication technologies not only empower people’s voices but also transcend established barriers. Hence, heterogeneous voices from in- and outside the country enter the discourse.

Authoritarian forces are struggling to contain non-conformity. The state, however, is less and less capable of suppressing expressions of alternate lifestyles. The urban Lao youth is especially attracted to various subcultural movements that shape distinct perceptions of the world they live in. Notions of a ‘good life’ are being reinvented and the youth no longer is willing to fully commit to the ideas of their elders. This poses a problem for the state, which is unable to communicate with its own youth. The most unruly of these youngsters, many from dysfunctional families, have often no choice but to escape established hierarchies and organize their own social networks. Gang members and street children now form a group of urban delinquents who are subject to incarceration. Thus, thousands of ‘rebels’ are detained annually in order to purge the streets of major cities of asocial behavior – a practice that can be observed especially before public events. This occurred during the Southeast Asian Games in December 2009, when beggars, street children, and suspected young troublemakers were detained to assure a perception of public order and coherence.

Much has to be done to face the spectrum of challenges in Laos. It is the duty of the Lao authorities to conduct thorough internal investigations, which serve to root out persons responsible for these distressing incidents and restore faith in the government. The international community should support efforts by progressive government officials and citizens in order to empower people’s voices. The global community should help to launch serious debates over the challenges that threaten social solidarity in Laos. Though progress faces a major setback with the disappearance of Sombath Somphone, the necessary dialogue has begun and will not be silenced easily. Mediators, like Sombath, will be needed to give voice to all Lao people, and who can bring together old and young, village and city, rich and poor. Only then, there is hope that genuine political representation will continue as it began – a liberation movement of the people, a means of attaining the aspirations of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.