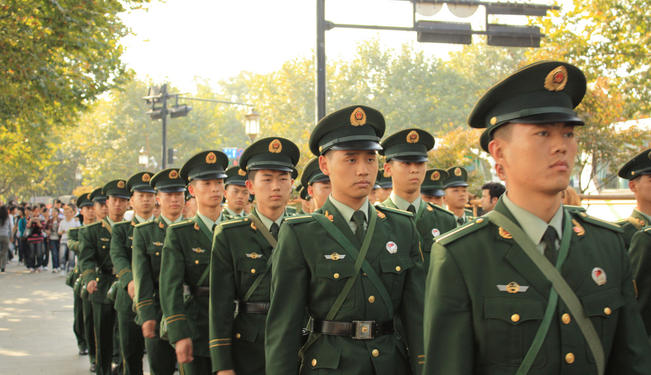

China’s recent military expansion has affected the country’s Asian neighbors and the People’s Liberation Army faces an array of future prospective security challenges. This is part II.

China’s Real Influence on Asia’s Strategic Landscape

While top American officials suggest that China’s buildup is excessive, the People's Liberation Army’s (PLA) modernization actually does not alter much of the strategic landscape of Asia. In examining the power structure of Asia, we should scrutinize East Asia specifically, because both the United States and China wield separate spheres of influence in the region. Contemporary East Asia is bipolar, split into continental and maritime regions. China has traditionally been a continental power, and will continue to retain its dominance of mainland East Asia. From the early 1970s to the end of the Cold War, elements of a strategic triangle composed of the United States, Russia, and China dominated the security landscape of East Asia. After the collapse of the Soviet Union China has stepped in to fill the power vacuum that was once permeated by a Soviet influence. On the Sino-Russian border, China’s conventional military capabilities are stronger than Russia’s, as Moscow’s inability to preserve its military infrastructure has reduced the strength of the Russian Army. Meanwhile, the United States has historically been unable to project its power onto mainland East Asia. As a result, China achieved dominance over mainland East Asia by 1991 and the modernization of its ground forces undoubtedly solidifies its authority as a continental power.

On the other hand, China’s buildup has not changed the power structure in the maritime region. The United States has been the leading maritime power of the Asia-Pacific region for at least 60 years and still retains its naval supremacy. America has acquired bases throughout East Asia. At the same time, because other countries do not have access to air and naval facilities in the same way that the United States does, they do not have either aircraft carriers or land-based aircrafts that can project power into the region. As a result, the U.S. Navy has comfortably dominated maritime East Asia. Even though the PLA has been expanding its navy in recent years, the net effect of China’s naval development on United States maritime superiority is insignificant. According to R.S. Ross in his article for The National Interest entitled “The great debate: Here be dragons”, the most important factor in evaluating the modernization of the PLA’s military forces is whether China is at the point of challenging the United States’ deterrences and making progress on war-winning capabilities to such a degree that maritime countries would doubt the value of their strategic alliances with the United States . He points out that even though China has been modernizing, it lacks the necessary technologies to become a great threat to the United States’ interests. Because the PLA’s modernization does not change the post-Cold War bipolar regional structure, which has been defined by Chinese dominance of mainland East Asia and U.S. dominance of maritime East Asia for the past 20 years, China’s buildup cannot be considered excessive.

A Tale of Two Islands

It is logical for China to build up its military forces because it is in a challenging security environment with Taiwan being China’s most serious security challenge. The Taiwan Strait remains a combative region due to it being the one region in East Asia where strong conflicts of interests persist and where both China and the United States have approximately equal and stable influence. China desires unification with Taiwan, while Taiwan pushes for independence. The United States, even though not formally endorsing either China or Taiwan’s position, asserts that its policy is to maintain peaceful cross-strait relations, and continues arms sales to Taiwan as part of the Taiwan Relations Act. Neither China nor the United States exerts complete hegemony over the Taiwan Strait. Since Taiwan is both an island and close to the mainland, its security is contingent on both China land-based capabilities and U.S. maritime capabilities. Peace in the Taiwan Strait depends on the deterrence dynamics between China and the United States, and both sides are prepared for military conflicts. Beijing maintains the deployment of short-range missiles across from Taiwan and it has purchased Russian military equipment in anticipation of a potential war with the United States over Taiwan. Washington, also bracing for a war with China in the Taiwan Strait, continues to expand the presence of its air and naval forces in the Western Pacific, sells arms to Taiwan, and bolsters its military commitments with Taiwan. Even though cross-strait relations have been relatively peaceful in recent years, Taiwan remains China’s leading security concern.

In addition to Taiwan, Japan is the second security challenge that China has to confront. In the post-Cold War era, instead of building its own military capabilities to defend its security, Japan has tightened its security relationship with the United States. One of the most important indications of this commitment was the Japanese agreement to the 1995 revised guidelines for U.S.-Japan military cooperation. These guidelines declare that Japan will commit to greater cooperation within the U.S.-Japan alliance, which allows the United States to rely on Japan to develop its own regional military power. China worries about the revised guidelines because the stated conditions imply that the United States will be able to access the Japanese facilities in a U.S.-China war over Taiwan. Since its agreement to the revised guidelines, Japan has improved collaboration with the United States in developing a missile defense system and bolstering naval cooperation. China views Tokyo’s intentions and expanding military capabilities with uncertainty and doubt. The Chinese concerns are further intensified due to the historical legacy of Japanese imperialism. China objects to Japan’s development of missile defense systems, claiming that these could threaten the Chinese strategic deterrent. In return, Japan also criticizes China’s missile deployments against Taiwan, saying that these missiles could strike parts of Japan.

Korean Peninsula Woes

An additional problem that China has to face is to maintain the status quo on the Korean Peninsula. As the Korean Peninsula is the only place in East Asia where the United States has kept a continental military presence, there is a prospect for greater power conflict. Since the United States, a traditional maritime power, perceives that its ground forces in South Korea are susceptible to a surprise attack, Washington has been counting on nuclear weapons to deter an attack. In his book Chinese security policy: Structure, power, and politics, Ross further argues that the US’ reliance on nuclear deterrence contributed to North Korea’s desire to acquire nuclear weapons. This status quo on the Korean Peninsula has been stable for more than 50 years and nuclear deterrence has been effective with minimum great power tension because North Korea exists as a buffer state between China and South Korea. As a result, Beijing has vital interests in working with Seoul and Washington to maintain the status quo. China has to worry about the collapse of North Korea for two reasons: First, the downfall of the North Korean regime would result in massive waves of North Korean refugees crossing the border into China’s northeastern provinces. Second, a unified Korea, under Seoul’s leadership and with the South Korea-U.S. security alliance still intact, would place a U.S. ally and possible future U.S. military bases next to China’s borders.

China and American Pressure

The likelihood of being contained by the United States and its allies in Asia is another concern that China has to consider. The United States possesses powerful military forces based on Taiwan, the Philippines, Japan, South Korea, and Thailand, which put the Chinese territory within the striking distances of U.S. forces. In addition, America has been strengthening its military power projection capability and continuing joint military exercises in the Pacific. China views these actions as an American attempt to build a firewall around China that might also improve Washington’s ability to pressure Beijing. China’s worries are further exacerbated by the Obama administration’s policy to return to Asia. This return was symbolically marked by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s decision to choose Asia as her first foreign visit destination. In the ASEAN Regional Forum foreign minister meeting in July 2010, Clinton advocated for the establishment of a multilateral mechanism for handling a settlement of the territorial disputes in the South China Sea. This proposal marked a breakthrough in U.S. policy toward the territorial contest, as Clinton articulated her opposition to China’s long-held and persistent position that it would only settle these disputes on a bilateral basis. To Beijing, Clinton’s comments indicated that Washington was siding with ASEAN countries. As America’s decision to return to Asia has been regularly seen as a reaction against China’s expanding influence in the region, China needs to confront the prospects of being encircled by a U.S.-led coalition.

Some may think that the PLA’s modernization could result in a potential power struggle between the United States and China, but the overall prospects for regional peace and stability are optimistic. As geography separates contemporary East Asia into a land theater and a maritime theater, the Chinese and U.S. spheres of influence are geographically distinct and divided by water. Therefore, an intervention by one power in its own sphere will not be as threatening to the interests of the other power in its sphere. This unique dynamic decreases conflicts over vital interests and alleviates the impact of the security dilemma, diminishing the possibility of high-level tension. Despite China’s buildup in recent years, the PLA’s modernization does not significantly alter this bipolar regional structure. As a result, even though there may be some low-level crises, Asia will continue to enjoy overall peace and stability.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer's editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.