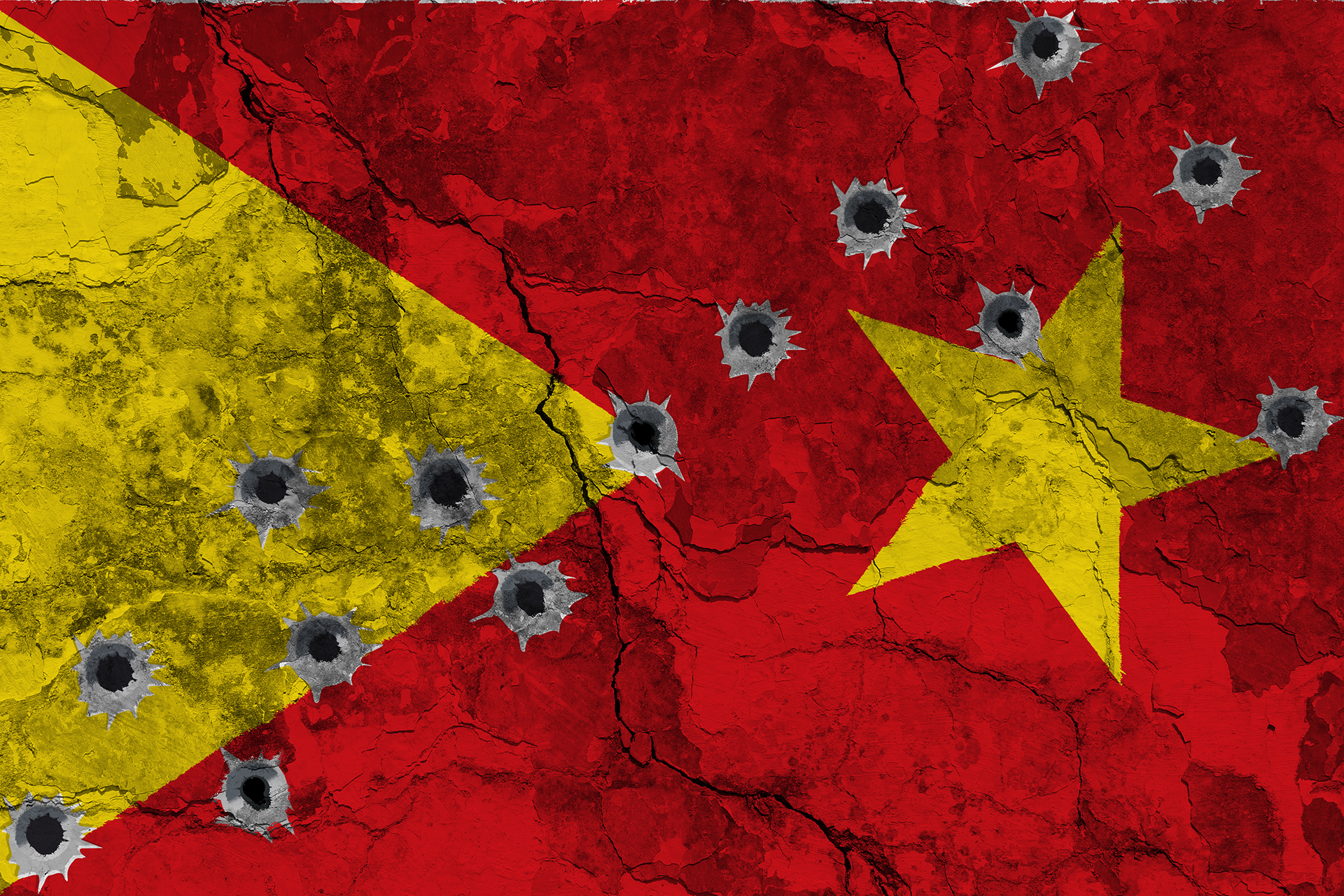

It was a dramatic indication that the war might be coming to an end. Two years of fighting between the Tigrayans and government forces from Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia, supported by regional militia have taken a terrible toll. The conflict is estimated to have resulted in the deaths of 250,000 troops. An estimated 383,000 to 600,000 civilians have died. Since it erupted the Tigray War has been the scene of the bloodiest, and one of the least reported, conflicts. Unlike Ukraine or Afghanistan, journalists have been forbidden from traveling to the front lines. So, no news has got out.

Peace in our time?

The peace deal was brokered in November 2022 in Pretoria and Nairobi. These agreements allowed for a ceasefire, aid flows and the deployment of African Union-led monitors who would oversee the re-establishment of Ethiopian government authority over Tigray.

The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the party that dominates the region, promised to disarm its fighters within 30 days under the agreement. That was signed on November 2. It has still not been completed, at least in part, because the text contained the provision that this would “depend on the security situation on the ground.”

As Patrick Wight wrote, the subsequent Nairobi agreement “states that disarmament of the Tigray Defence Forces’s heavy weapons will be “done concurrently with the withdrawal of foreign and non-ENDF (Ethiopian National Defence Forces) from the region.” What a “concurrent” disarmament of TDF and withdrawal of Eritrean troops looks like in practice is anyone’s guess. It would be positive if this means the alarmingly rapid disarmament provisions agreed to in Pretoria will be delayed.

It has been the Eritreans that have been holding up progress. At the end of December there were eyewitness reports of Eritrean forces leaving Tigrayan towns. “Eritrean soldiers, who fought in support of Ethiopia’s federal government during its two-year civil war in the northern Tigray region, are pulling out of two major towns and heading toward the border, witnesses and an Ethiopian official,” Reuters reported.

Others are less certain. Tigrayan refugees fear that the Eritreans remain in parts of the region. Tigrayans have posted photographs of Eritreans in Tigrayan cities on Twitter, including Adwa.

Meanwhile, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki has been claiming “victory” for his forces over the Tigrayans. “My pride has no bounds”, he said in his New Year message. But the Eritrean leader is taking no chances. He is reported to be training dissident Ethiopians in case his relationship with Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed goes sour.

Afwerki previously used foreign troops to threaten neighboring leaders with the use of force. In 2011, the United Nations reported that Eritrea was behind a planned “massive” attack on an African Union summit in Addis Ababa, using Ethiopian rebels. It would be wrong to assume that a similar attack is now on the cards, but training dissidents could be a tactic to maintain pressure on Ahmed.

Maintaining tension and instability across the Horn of Africa has been a tactic the Eritrean leader has used consistently since capturing Asmara, the Eritrean capital, in 1991. Since then, Afwerki has led his country into no fewer than eight different conflicts – from Somalia to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

How will Europe and the US respond?

US President Joe Biden has been assiduous in attempting to end the fighting in Tigray. Biden appointed special envoys to the Horn of Africa as soon as he came to office. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken went out of his way to meet Ahmed during the US-Africa summit in December. He raised the question of peace with Ahmed as well as the ending of the Eritrean troop presence in Tigray. Some wags have suggested that the peace agreements signed in Pretoria and Nairobi were so closely linked to Washington’s efforts they should be termed “US solutions to African problems” – clearly, a play on the phrase “African solutions to African problems.”

Who Can Resolve Ethiopia’s Catastrophic Conflict?

The key question now is whether sufficient progress has been made to lift the American and European sanctions against Ethiopia. They were introduced to try to end the war. In the words of Jeffrey Feltman, the former US special envoy to the Horn: “The United States and the European Union hoped that, combined with emergency humanitarian assistance, punitive measures such as the threat of sanctions and the withholding of development aid would halt the atrocities and move the parties from the battlefield to the negotiating table.” While the two parties did come to the negotiating table, it is unclear if the peace in Tigray is sustainable.

After two years of war, Ethiopia’s economy is said to be on the verge of collapse. The country needs nearly $20bn for its reconstruction. The EU Foreign Affairs Council is due to meet Brussels on January 23 and one of the issues on their agenda is the possible unfreezing of hundreds of millions of euros pledged in aid to Addis Ababa. Since 2021, the EU froze nearly $210m in aid to Ethiopia, following the draconian blockade Addis Ababa imposed on the Tigray region. The money is badly needed and it is not yet clear what strings the Europeans may attach to the lifting of sanctions.

For Eritrea, the picture is clearer: Washington has no time for Afwerki and is likely to keep the president under pressure. Afwerkid is already so isolated that it is unlikely that he cares greatly about western attitudes. He prefers to rely on his Arab neighbors, China and possibly Russia for international support. Eritrea will keep playing its game of promoting Ethiopian rebels to retain relevance in the region. This is bad news for Ethiopia and prospects of peace.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.