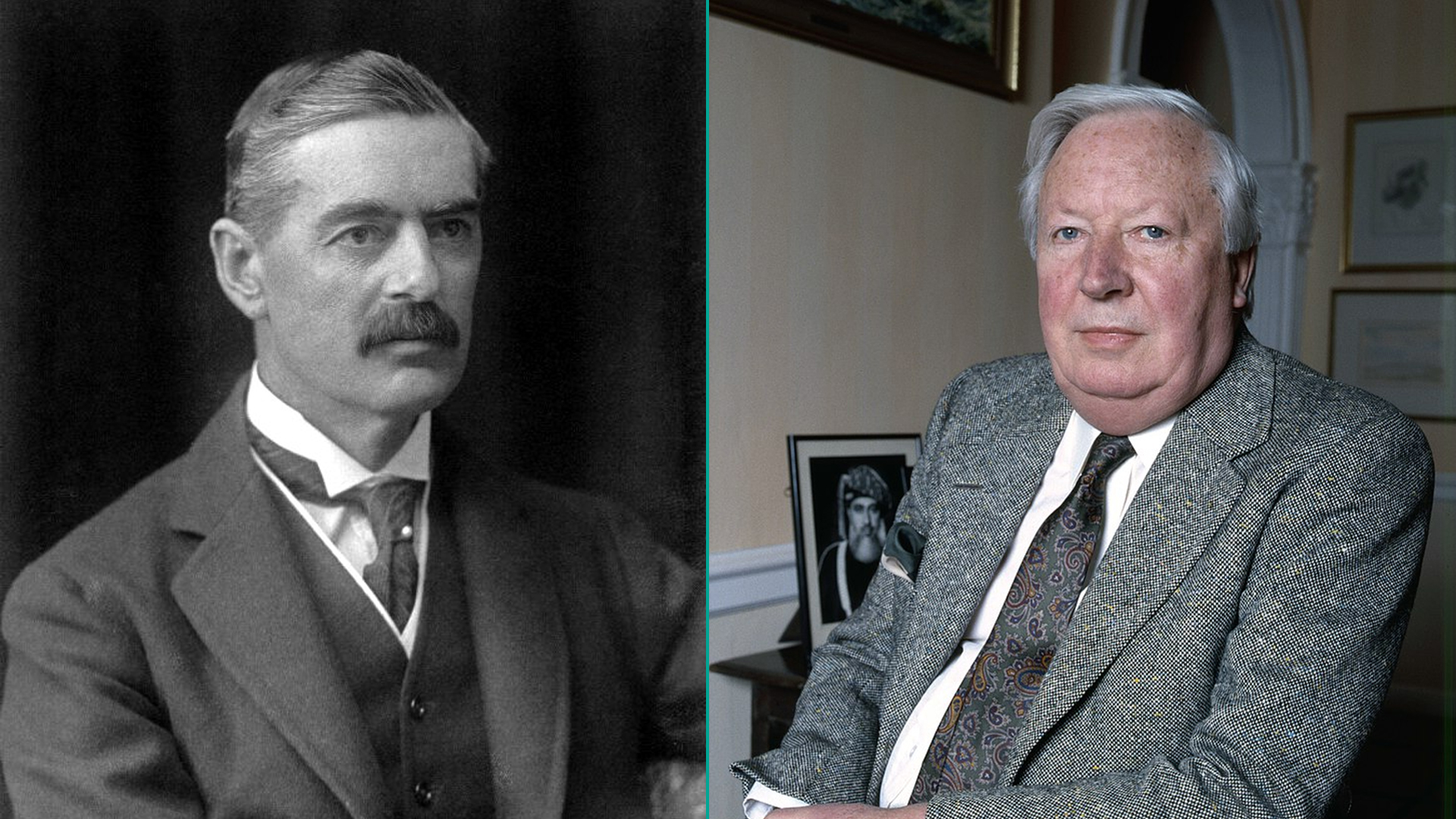

I have just finished reading two very well written books about Neville Chamberlain and Edward Heath. Both were Conservative prime ministers in the 1930s and in the 1970’s respectively.

Nicholas Milton is the author of Neville Chamberlain’s Legacy: Hitler, Munich and the Path to War. This biography published by Pen and Sword in 2019 is a new look at this British prime minister and his times. Edward Heath’s autobiography, The Course of My Life, was published by Hodder and Stoughton in 1998.

Chamberlain and Heath’s political lives span the period of British history from 1920 to 2000. Both these books are a good introduction to this period. They reveal how the priorities and the philosophy of a major political party adapts to changed circumstances.

Looking Back at Neville Chamberlain

Neville Chamberlain is, of course, remembered for his attempts to find a modus vivendi with Hitler. He forced Czechoslovakia to make territorial concessions to Nazi Germany and is blamed for the policy of appeasement. However, this book rightly shows us that there was much more to Chamberlain than just this moment in history.

This British leader was minister for health in the 1920s and was responsible for initiating a huge programme of social housing. He introduced pensions for widows. In modern terms, he was a “leveling up“ leader who did what he said. Chamberlain was not impeded by free market dogma. He had been a local councilor and mayor in Birmingham before entering the House of Commons. This leader had seen poverty first hand. Therefore, he instituted policies to address this issue.

Contrary widely held perceptions, Chamberlain was no pacifist. As the chancellor of the exchequer after the 1936 general elections, he imposed a three pence income tax on the pound to pay for more defense spending, particularly of aircraft. This investment proved critical during the Battle of Britain and Chamberlain gets little credit for it.

When it came to negotiating for peace, Chamberlain failed to understand Adolf Hitler. The Nazi leader was a reckless gambler who did not play by the rules of the game. Chamberlain mistakenly assumed that Hitler was a normal calculating politician and acted accordingly.

Yet it is important to remember that Chamberlains did buy significant extra time for British rearmament by appeasing Hitler in 1938. He was also reflecting the zeitgeist. On September 24, 1938, The Irish Times published an editorial saying that Chamberlain “has the sympathy and admiration of the whole civilised world, because he has done more than any other individual to save mankind from another war.” The editorial went on to say that the British prime minister “has done what no other statesman in Europe would have the courage to do.”

Éamon de Valera, the Irish prime minister from 1937 to 1948, admired Chamberlain’s policy as well. The British prime minister was not alone in subscribing to a policy that eventually failed. Peace in Europe, which many fervently desired after the horrors of World War I, was not to last. Chamberlain failed in his goal to maintain this peace and this failure was clear to him before he died in 1940. Yet the late prime minister deserves credit for many of his other policies and his service to his nation.

Edward Heath’s Story

The great goal of Heath’s political life also was peace in Europe. He sought to reach that goal by bringing the UK into the EU. For him, the EU was a structure of peace in Europe, binding countries so closely together economically that they could never contemplate war with one another. Fortunately for Heath, he did not live to see his work partly undone. He died in 2005, more than a decade before the UK voted to leave the EU in the 2016 referendum.

Heath was an excellent writer. His autobiography keeps the reader’s attention over its full 736 pages and gives a good account of his personal life. Heath was brought up in a semi-detached house on the Kent coast. His father was a qualified carpenter who made a living as a small builder.

Heath became an undergraduate in the University of Oxford before World War II on the basis of his academic results. Like many British leaders, he became active in politics during his time at Oxford and joined the student Conservative Party. As a student politician, he opposed Chamberlain’s appeasement politics. Heath had observed Hitler’s Nuremberg rally in person.

Heath served in World War II bravely. He gives an entertaining account of his search for a parliamentary seat after the war. One association wanted an assurance that Heath would reply to all correspondence personally, and in longhand, as the previous member of parliament (MP) had done. Heath would not give that assurance, so he had to look elsewhere. Another wanted an MP who might become a minister.

Heath finally found a seat in Bexley, Kent on the eastern edge of London. He was elected to serve that constituency in the general elections of 1950. Heath served the constituency loyally as its MP and Bexley remained loyal to him too despite his public differences with Margaret Thatcher who ousted him from the Tory leadership in 1977.

Heath devotes much of the book to his work in negotiating British entry into the EU. He points out that the true political nature of the EU was set out for the British people. It was not presented merely as an economic arrangement. This was done before the House of Commons voted to join the EU and over 67% of British voters opted for joining the EU in the 1975 referendum. This stands in stark contrast to the 2016 referendum, where spin, misinformation and downright lies were rife in the political campaign.

Heath also gives his version of his difficult relationship with Thatcher. Early in their career, Heath and Thatcher had much in common and were good friends. It is a pity she did not find an opportunity to bring him back into government at some stage after she replaced him as the leader of the Conservative Party. Yet Thatcher might have had a good reason for her decision. Heath may have expected too much too soon.

The breach between the philosophies of Heath and Thatcher remains unhealed. For now, Thatcher’s version of conservatism is triumphant.

Observations on Chamberlain and Heath

The title of Milton’s book suggests that he is assessing Chamberlain’s legacy. The biography does not do so.

My own assessment of Chamberlain’s legacy is that he gave appeasement a bad name. His failure to avoid World War II in 1938 has shaped British and American decisions since. When negotiating with dictators or authoritarian regimes, British and American leaders have often begun with wrong assumptions and made poor decisions. For example, Saddam Hussein was bluffing about the weapons of mass destruction. Yet British and American leaders were haunted by the ghost of Hitler and went to war on a false claim. This perceived failure of Chamberlain has led to many failures since World War II.

Milton’s book also deals very slightly with Chamberlain’s policy towards Ireland. He settled the economic war between the UK and the Republic of Ireland in 1938 on financial terms that were favorable to Ireland. Sadly, this has been forgotten in Ireland.

Following the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922, the UK retained three deep water Treaty Ports at Berehaven, Spike Island and Lough Swilly in accordance with the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 6 December 1921. Chamberlain gave Ireland back these Treaty Ports, which enabled the country to remain neutral in the war. The biography does not explore this far-reaching decision either.

In his book, Heath devotes a chapter to Ireland. He was the first British prime minister to say that the UK had no selfish interest in Ireland. He was the first to visit Ireland when he met Liam Cosgrave in Baldonnel in 1973. Earlier British prime ministers over the previous 50 years had expected their Irish counterpart to visit them in London. Heath’s visit was symbolic and historic.

As prime minister, Heath approved the introduction of internment without trial by the Stormont government in Northern Ireland. He justified this decision on the grounds that juries would be intimidated. Yet he seems to have given insufficient thought and not explored alternatives to the consequences of this radical decision.

Heath sought to end the conflict in Northern Ireland through the 1973 Sunningdale Agreement. This was an attempt to establish a power-sharing Northern Ireland Executive and a cross-border Council of Ireland. In his autobiography, Heath claims that Liam Cosgrave, who was then the Irish prime minister, lacked the courage to promise to hold a referendum to remove articles 2 and 3 of the constitution. These articles included a territorial claim by Dublin to rule Northern Ireland. Removing them was to be a price to be paid for setting up a Council of Ireland with consultative functions.

Given that the partition of Ireland had been accepted in practice by Dublin as early as 1925, this territorial claim should never have been inserted in the Irish Constitution of 1937. However, once this claim was in the constitution, removing it was bound to be divisive.

Heath seemed to have forgotten that Cosgrave headed a coalition government and that some of his strong-minded ministers were quite nationalistic. The main opposition party, Fianna Fail, was even more nationalistic. The risk of defeat in such a referendum on the constitution and split in the government was extremely high. Cosgrave’s government could have fallen on this issue and his hands were tied. So, lack of courage is the last thing of which Cosgrave can be accused. Heath’s evaluation of Cosgrave demonstrates that even enlightened British leaders sometimes have a poor understanding of Ireland.

Both Chamberlain and Heath had hobbies that helped them keep their minds relaxed despite the pressures of the job as prime minister. Chamberlain’s interests were angling, birdwatching, and the study of moths and butterflies. Heath’s interests were music and sailing, and he reached a very high standard in both activities.

In their own ways, both prime ministers were far-sighted statesmen. Like all human beings, they had their faults and made mistakes. However, it is important to remember some of their significant achievements.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.