Up until April, the COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore had largely been kept under control, to the extent that it was considered one of the best examples of pandemic response in the world. By speedily rolling out measures — including contact tracing, aggressive testing and isolating potential carriers — the Singaporean government had done well enough to merit significant praise from international observers and the World Health Organization.

Yet, despite signs that all was going well, on March 23, a letter was published in the Straits Times by a Singaporean migrant workers’ rights group, TWC2, highlighting the significant dangers posed to their community. “Migrant worker” in this context specifically refers to low-wage foreign nationals engaged in construction, public utilities maintenance, cleaning and other relatively labor-intensive areas of work. In particular, the group pointed out the dense, clustered accommodation in dormitories and the restrictive policies by employers that put these workers at a high risk of contracting and spreading the coronavirus.

Rohingya Refugee Camps Are the Next Frontline in COVID-19 Fight

In hindsight, the letter was prophetic. Less than two weeks later, infection clusters began to form in dormitories across the island. As of now, more than half of all the cases in Singapore have been attributed to migrant workers, leading to an exponential jump in infection numbers even as Singapore waits to be released from its “circuit breaker” lockdown protocol.

Left Out

Around the world, migrant workers suffer amidst the pandemic. In India, hundreds of thousands of out-of-work day laborers have trekked across the country — in what is the biggest exodus since the Partition crisis of 1947 — in an attempt to reach their homes. This massive movement of people, sparked by fears for their livelihood, has already claimed lives and added to the state and federal governments’ worries. In Thailand, they have been left out of the government’s pandemic response, unable to either stay due to lack of work or return home because of closed borders. Facing financial uncertainty, there are fears that migrant workers will simply move around the country in search of jobs. In the Middle East, migrant workers still remain in lockdown in crowded, unsanitary camps.

It is clear that not enough has been done to ensure not just their safety, but their very ability to survive. Four factors compound to amplify the disproportional risk migrant workers must bear during the pandemic. First, migrant workers are over-represented in physically demanding and labor-intensive jobs such as construction, agriculture and maintenance, which often conform to the 3D term of being “dirty, dangerous, and demeaning.” Their day to day involves close contact, inadequate sanitation and lengthy travel — all potent vectors for the spread of the virus.

Second, remuneration from these same jobs often does not guarantee an adequate standard of living, with migrant workers largely sending their already meager low salaries home to their families. Oftentimes, as is the case in Singapore, Bangladeshi migrants must make payments of up to $12,000 to their agents simply to secure a job. Such financial stresses place limits on their financial flexibility to protect their own health.

Third, as mentioned earlier, migrant workers often have no other option but to put up with communal living in dormitories and other similar forms of housing, which hastens the spread of viral infections. Constrained by low income, such housing methods allow for more effective control by their employers and agents. In this case, cramped living makes adequate social distancing virtually impossible, increasing the likelihood of virus clusters.

Lastly, and most significantly, migrant workers are prone to exploitation by their employers. As highlighted by TWC2, some examples of how migrant workers may be exploited include their precarious legal status, restrictions from changing jobs, illegal deductions from their salaries, employers’ refusal to pay their medical bills and the risk of forced repatriation. In the Middle East, the kafala sponsorship system, which requires employers to sponsor workers, forces laborers into a relationship of total dependency on their employer.

Moreover, as foreigners, migrant workers often become victims of racial or social discrimination from society. Unfamiliar with local customs or unable to speak the language, many are cut off from all lines of support and find themselves pressured into accepting their employers’ policies or rules. Some of these policies include being forced to turn up for work in spite of illness and paying for their own medical treatment, all of which incentivize behaviors conducive to the spread of the virus.

All at Once

Individually, physical labor, low wages, communal living and exploitation are all issues that can be experienced by many other groups in society. What makes migrant workers special is that they are the only group to be most commonly subject to all four at once.

When it comes to the financial aspect, UK think tank IPPR notes three more reasons why migrant workers are at risk during the pandemic. They tend to work in sectors such as the construction industry that are particularly vulnerable during an economic recession. They often have less access to public funds due to their special work status in a foreign country. They are also often more willing to continue work in compromised circumstances. Given this long list of vulnerabilities, migrant workers should have been prioritized in any decent pandemic response. Why have they continued to be overlooked?

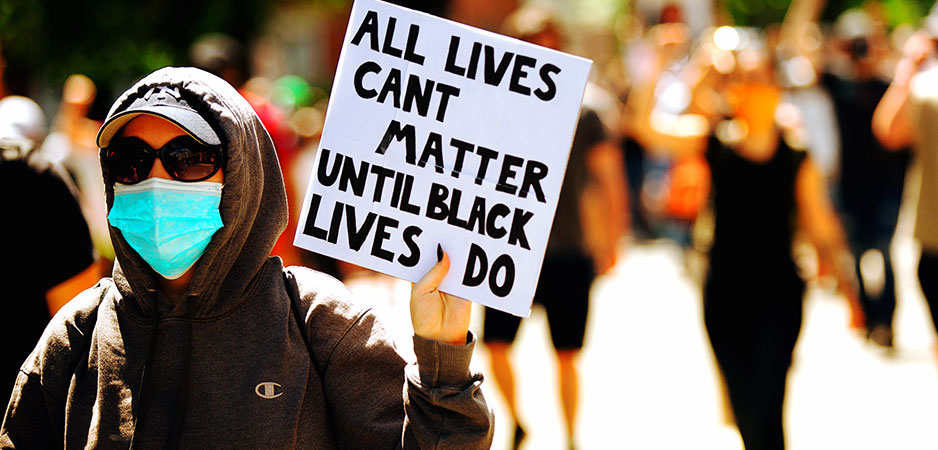

Some issues point squarely toward the mentality of societies that accept these migrant workers. It is hard to ignore the role racism plays in discrimination against migrant workers. Not long after the dormitory clusters became an issue, a controversial letter was published in Singapore’s Chinese-language newspaper, Lianhe Zaobao, attributing the outbreaks to their “personal hygiene and living habits,” implying the backwardness of their countries of origin — predominantly India, China, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Myanmar and the Philippines.

Singapore’s law and home affairs minister, K. Shanmugam, denounced the letter as “typecast[ing] an entire group” and effectively using this prejudice to blame the victims for their own plight. But the fact that the letter was even published speaks volumes of public attitudes.

Moreover, migrant workers are often employed in occupations considered to be “beneath” the local population. There is sometimes an outright reluctance to engage in such jobs. In the UK, for instance, when locals were called upon to help fill over 70,000 seasonal agricultural positions, there were only 35,000 expressions of interest, with just 5,500 willing to proceed to the interview stage. Such attitudes expose an unspoken arrogance and societal segregation that excludes migrant workers from the rest of the community.

The Changing of Attitudes

However, while sentiments of racism or arrogance do exist, most people admit that many of their daily comforts are reliant upon the labor provided by migrant workers, which promotes an implicit culture of acceptance of these workers as critical to the functioning of society. It might be more accurate to describe the attitude as one of apathy, which quietly acknowledges the problems migrant workers face but lacks popular motivation to do much about it.

But with the pandemic now shining the light on the importance of what we now call “essential,” and previously “low-skilled,” workers, there is an overdue impetus for change. In Singapore, a petition to the Ministry of Health calling for better conditions for migrant workers has already gathered over 70,000 signatures. A community initiative named MaskForce has also recently been formed to provide migrant workers with the masks they need.

Of course, it is difficult to imagine a simultaneous, massive worldwide revolution in the treatment of migrant workers. However, the common struggles faced by everyone during this time of crisis can hopefully breed greater solidarity with those who keep our essential services running. For the rest of society, lockdowns and the struggles of everyday life have sparked a greater openness to new ideas and ways of doing business, such as what some are calling a work-from-home revolution. Hopefully, this greater openness can also lead to tackling the apathy that enables the exploitation of migrant workers around the world and initiate the long-term strengthening of their rights.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.