When Pakistan was formed in 1947, it included two parts: West and East Pakistan. These two parts of the country were approximately 1,600 kilometers apart. Between them was India. The two parts of Pakistan were divided by more than distance. The biggest linguistic group in East Pakistan were Bengalis who spoke Bangla. The biggest linguistic group in West Pakistan were Punjabis who spoke Punjabi.

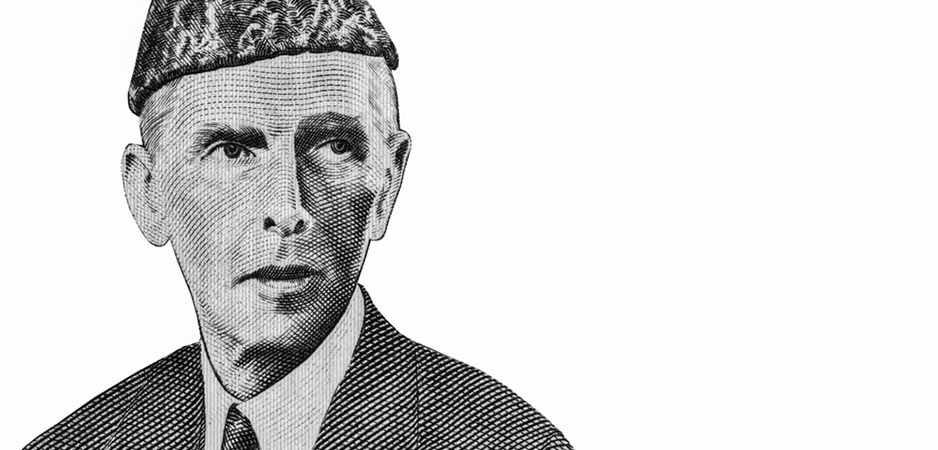

Newly-independent Pakistan chose neither Bangla nor Punjabi as its national language. Instead, it chose Urdu. At Dhaka University’s convocation on March 24, 1948, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, gave an iconic speech that is quoted till today: “In my personal opinion, Pakistan’s official language — which will become a source of communication between its different provinces — can only be one and that is Urdu. No language other than Urdu.”

Han and Hindu Nationalism Come Face to Face

This stance caused tensions with East Pakistan because Bengalis were rather attached to their language. On February 21, 1952, less than four years after the Jinnah’s speech, Pakistan brutally cracked down on those demanding the adoption of Bangla as the second national language. The state arrested and killed many students, teachers and intellectuals at Dhaka University. Many other developments exacerbated Bengali resentment and East Pakistan broke away from Pakistan. It emerged as the independent nation of Bangladesh in 1971 and promptly chose Bangla as its official language.

Urdu Waxes, Punjabi Wanes

The official language of Pakistan continues to be Urdu. Curiously, this language is the mother tongue of only 7-8% of Pakistanis. Of 213 million Pakistanis, Punjabi is spoken by 48-55% of the population. The reason for such a wide range is the debate over Saraiki. Some consider it a dialect of Punjabi, while others treat it as a separate language.

Punjabis dominate the Pakistani state and society at all levels from politics, bureaucracy and the ubiquitous military to economics and culture. Despite the domination of Punjabis, Pakistan has employed Urdu as a medium of instruction since its inception. The teaching of Punjabi in schools is prohibited. All official business of the state is conducted either in English or in Urdu. In fact, Pakistan’s 1973 constitution recognizes Urdu as the country’s only national language.

In the 1980s, some intellectuals began a daily newspaper in Punjabi. Named Sajjan, the newspaper’s first issue came out on February 3, 1989, but it lasted merely 20 months because neither the government nor the private sector filled its coffers through advertisements or public notices. Until the early 1990s, members of the Punjab Assembly, the state legislature, were forbidden to address the house in Punjabi. This ban was temporarily removed by the writer Hanif Ramay who, at that time, was the speaker of the assembly. However, the ban was revived afterward.

Some valiant champions of Punjabi continue to propagate the cause of the Punjabi language, but this has been confined to small intellectual circles. They have been demanding that Punjabi be taught in school at the primary level, but no government has accepted the idea. The Punjabi language, therefore, is relegated to informal day-to-day communication. A key question arises: Why have Pakistani Punjabis disowned their mother tongue?

Clues From the Past

We need to find clues in the peculiar cultural and political evolution of Punjab. The Punjabi language belongs like most others of northern India to the Indo-European family of languages. It began to be used in literary communications and in writings from at least the 13th century. Farid al-Din Masud Ganj-i-Shakar, a noted Sufi saint popularly known as Baba Farid, is said to have written in Punjabi using the Persian script. That tradition was continued by later Sufis such as Shah Hussain, Bahu Shah, Bulleh Shah and Waris Shah. In the 19th century, the likes of Mian Muhammad Bakhsh and Khawaja Ghulam Farid enriched the Punjabi literary tradition even as they used the vernacular to connect with ordinary people.

Punjabi was also adopted by another faith. When Guru Nanak founded Sikhism in the early 16th century, Punjabi became the language of a community that consolidated as a religious community under his spiritual successors. Sikhism adopted Gurmukhi, a distinct script devised by Guru Angad, the second of the 10 Sikh gurus who succeeded Guru Nanak. In contrast, Hindu Punjabis continued to use the Devanagari script and used Sanskrit for their religious ceremonies.

During much of the time of Sikh gurus and Sufi saints, the official language of Punjab was Persian. The state officialdom largely hailed from the Turco-Afghan nobility and conducted their affairs in Persian. This nobility owed loyalty to the ruler of Delhi and, later as the Mughal Empire declined, to the master of Kabul. In northern India, the common lingua franca was Hindustani. In literary usage, this language either took the form of Hindi written in the Devanagari script or of Urdu penned in the Persian script. Toward the end of Mughal rule, Urdu began to be cultivated by the urban literati even as Persian continued to the official state language.

When the British emerged as the ruling power in India, they decided to adopt Urdu as the language of the state at the lower level, especially in the army. On April 2, 1849, the British annexed Punjab 10 years after the death of Ranjit Singh, the founder of a Lahore-based Sikh empire. To facilitate their administrators, they enforced Urdu as the vernacular language instead of Punjabi. Urdu was the state language in the army and other lower levels of government.

In the religious and communal revivals of the 19th century, Hindi came to be associated with Hindus, Urdu with Muslims and Punjabi with Sikhs. Yet spoken Punjabi is the shared vernacular of all Punjabis, cutting across religion, sect or caste. Even today, the language continues to be the day-to-day medium of communication and interaction.

The religious revivals of the 19th century have to be examined in the wider context of the anti-colonial freedom movement of the 20th century. The Indian National Congress (INC) claimed to represent all Indians irrespective of religion. It declared Hindustani, the common vernacular of north India with the Devanagari and Persian scripts, as the national language of a future independent, united India. The All-India Muslim League rejected the INC’s claim to represent all Indians. Instead, the Muslim League, as it has come to be known, claimed to represent all Indian Muslims. It rejected Hindustani as the national language and declared Urdu to be the official language of Indian Muslims.

Two states emerged when Indians won independence: India and Pakistan. The partition of British India in 1947 was brutal and bloody. The two Muslim-majority provinces of Bengal and Punjab were divided between India and Pakistan. Refugees fled from one country to another. The Urdu-speaking migrants from India came to be known as Muhajirs and were initially overrepresented in the central government. However, Punjabis dominated young Pakistan and its powerful military. Once Bangladesh seceded, Punjabi domination strengthened.

These Punjabi Muslims adopted Urdu because the language had been the lingua franca of Pakistan since 1947. Since 1971, Urdu became further entrenched. It became the language of middle and lower-middle-class Punjabi intelligentsia. Upper-class Punjabis like other upper-class South Asians were educated in English and had little love for vernacular languages or literature. The movement to introduce Punjabi instruction in school has failed despite Punjabis wielding most levers of power in Pakistan. It is because the Punjabi elites have given up on its language and adopted two other languages supposedly more sophisticated and modern than their native tongue.

The Problem With a National Language

It is worth mentioning that Pakistan is not alone in facing a problem with a national language. All states must choose one language to signify national identity and to conduct their affairs in an efficient and coherent manner. In multi-language societies, the choice of national or state language is always problematic. An apt example is Turkey where the Turkish language alone is declared as the state language. It has resulted in considerable resistance by the Kurds, a people proud of their identity and language.

Tiny Israel has also found the issue of a national language thorny. The founders of Israel were European Ashkenazi Jews who either spoke Yiddish or the national languages of the countries where they had grown up. In a radical choice, Israel decided to make Hebrew its national language. Hebrew was the ancient language of Jews and had not been spoken for centuries. So far, it seems that Israel has succeeded in its national language policy.

In India, partition led to the abandonment of Hindustani as the national language. Instead, the country’s officialdom increasingly uses a Sanskritized form of Hindi, even as most young people speak a mixture of Hindi and English termed Hinglish. Nevertheless, the rise of Hindu nationalism and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has strengthened the use of Sanskritized Hindi in government. Most North Indians continue to speak Hindustani, which is also the preferred language of Bollywood, India’s multibillion-dollar film industry.

In the light of these examples, the case of Pakistani Punjabi elites and intelligentsia adopting Urdu as their language of written communication and formal speech makes sense. Urdu may only be the mother tongue of a small minority, but it is tied up with Pakistani identity. Also, Pakistani Punjabi elites are able to defuse tensions with smaller nationalities such as Sindhis, Pakhtuns and Balochis who resent Punjabi domination. Punjabi elites can reasonably point out that they are not imposing their language on minority nationalities.

Despite Urdu being Pakistan’s national language, people prefer to speak in their native tongues. In Punjab, educated elites in Lahore and Islamabad might speak either English or Urdu or both. However, the rest of the people converse in Punjabi. It might no longer be the written language of the state. Newspapers, novels, poems and high literature in Punjabi might be in short supply, but the oral language runs strong. Elven elites find its uses even though they treat it as a pariah tongue, useful to connect with the uneducated masses or to express crude humor and abuse.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.