In this edition of The Interview, Fair Observer talks to Andrew Yang, a Democratic presidential candidate for 2020.

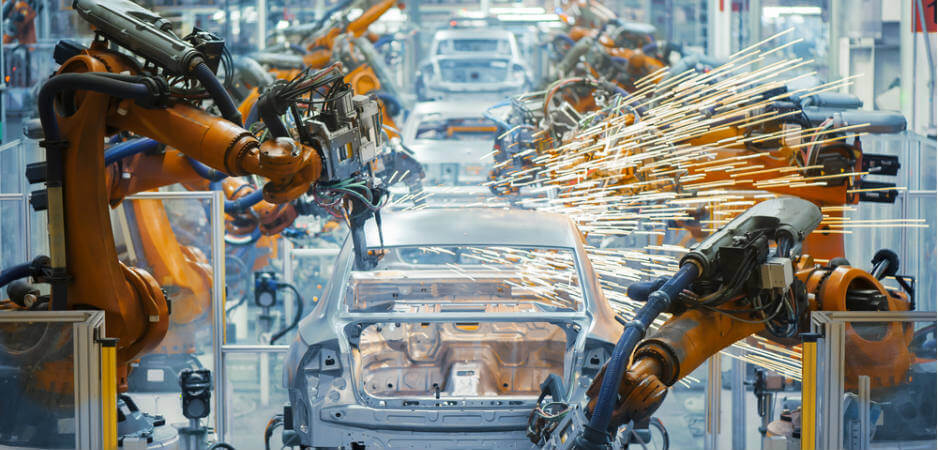

Andrew Yang is the founder of Venture for America. The nonprofit organization trains young, aspiring entrepreneurs to build businesses in emerging cities across the country such as Detroit, Cleveland and Baltimore. Now, he is running for president of the United States. Yang believes that the advent of automation poses a serious risk to American jobs. In the past several years, he’s seen automation wipe out jobs in manufacturing and truck driving. Even workers in retail, accounting and journalism are under threat from technology. For Yang, the solution is a universal basic income.

A 2017 study by the consulting firm McKinsey & Company predicted that between 400 million and 800 million jobs may become automated by the year 2030. Yang proposes the so-called Freedom Dividend — a $1,000 monthly income for every American aged 18 to 64. This amount raises every individual roughly to the poverty line.

Pilot programs for universal basic incomes have been launched in the past in Finland, Kenya, Canada’s province of Ontario, and cities like Barcelona and Oakland, among others, and with varying degrees of success. Furthermore, tech moguls like Elon Musk, Marc Andreessen and Mark Zuckerberg have all expressed support for a universal basic income. Former President Barack Obama and Senator Bernie Sanders too, have floated with the idea. A recent Gallup poll found that 48% of Americans are sympathetic to a basic income as well.

In this edition of The Interview, Fair Observer talks to Andrew Yang about his vision for the United States, the social stigmas of a universal basic income and the failings of the Democratic Party.

Naveed Ahsan: Why have you decided to run for president?

Andrew Yang: I spent six and a half years running an organization called Venture for America, and our goal was to create thousands of jobs around the United States, which we did successfully. I came to realize that we were pouring water into a bathtub that has a giant hole in the bottom. Right now, the United States is in the process of automating away hundreds of thousands of jobs in its most common job categories.

The country started with manufacturing, which is what I saw much of when I was working in the Midwest. That led to Donald Trump’s election in 2016 after we automated 4 million manufacturing jobs in Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. We’re about to do the same thing in jobs in retail, call centers, fast food and truck driving.

So I did not imagine myself getting into politics. But if you can, put yourself in the shoes of someone who’s trying to create jobs, then realize that those jobs are going to be wiped out in large numbers and then realize that it’s going to be increasingly disastrous for the country. That’s when I decided to run for president.

Ahsan: Why is a universal basic income the solution?

Yang: One of the problems people are having in the US as that they don’t like to look at the true facts of the transformation of our economy and the labor force — particularly because they are afraid to spend money. Most often they’ll say that the solutions are too large in terms of what it would take to meaningfully change our economy. So they shy away from it.

But if you look at the facts, you realize that we need to dramatically evolve in terms of the way we both seek and distribute work and value in the US. Just look at one labor category, like truck drivers. There are 3.5 million truckers, 94% are male, the average age is 49, and their average education [level] is high school. If you foresee that a significant number of those jobs are going to be lost to robot trucks in the coming years, there are very few ways to help that population transition other than something like a universal basic income.

One thing that I am confident of is that worker freedom and bargaining power will go up in a world where people are receiving basic income because the fear of being indigent on the street will have disappeared.

I’d also suggest that the most dramatic thing about universal basic income is the effect it would have on individual family and households. You can see very clearly in previous applications that children’s health and nutrition improves, graduation rates rise, mental health improves, domestic violence goes down, hospital visits go down. So, even though I am starting with a macroeconomic perspective, it’s most compelling what happens at the personal level.

Ahsan: Under your plan, how will the country pay for a universal basic income scheme?

Yang: The single biggest move that the United States has to make is that right now our income-based tax system is really bad at harvesting the revenue from new technologies and artificial intelligence because the beneficiaries will tend to be very big tech companies that are very good at not paying a lot of income tax.

What America has to do is that it has to join the rest of the developed world and have a value-added tax. The American economy is now so vast at over $19 trillion, which is up $4 trillion in the last 10 years alone. We could easily generate almost $1 trillion in revenue with a value-added tax, in combination with existing spending, economic growth due to putting money into people’s hands, and efficiency improvements.

Ahsan: One common objection to implementing a universal basic income is that it will destroy one’s incentive to work. What is your response?

Yang: That very line of thought presupposes that extreme scarcity is why anyone does anything — that if somehow you were to remove the threat of starvation, none of us would do anything. So the first thing is that the data does not suggest that is the case.

If you look at situations where people have received basic income support, work levels have remained essentially constant. The only populations that are working less are new moms who spend more time with their children and teenagers who graduate at higher levels — which, I guess, most people would be pretty happy to hear.

So the facts do not indicate inter-mass slothfulness if people are receiving a basic income. The second thing is that virtually no one can flourish on a $1,000 a month, which is the level I am proposing in my plan with the Freedom Dividend. The third thing is that it will actually push people to do more forms of work that we need more of and that people find more meaningful.

Ahsan: Many would also argue that, historically speaking, automation will not lead to anything new. People have always adapted to major technological shifts. Why do you think automation is different?

Yang: Most people that use that line of argument refer to the Industrial Revolution. If you look at the history of the Industrial Revolution, you find that there were mass protests and riots of violence, including strikes that killed dozens of people and caused billions of dollars worth of damage. The US then implemented universal high schools in response and inaugurated Labor Day as a celebration of the laborers who were agitating for more rights. So even if you were to use the Industrial Revolution as your template, you would foresee mass protests and violence.

There’s all this happy talk and optimistic thinking that people are going to miraculously adapt to different circumstances, but there are many, many Americans who are going to struggle to adapt. It’s really the vast majority. If you look at the numbers, 58% of Americans are essentially high school grads, 42% have a two-year degree, and only 32% have a four-year degree. Many Americans who are working in these jobs are middle-aged. So imagining that this population is somehow infinitely re-trainable, and mobile and resilient, is wrong. The fact is, if you look at studies on how effective government-sponsored retraining programs are, you’ll find that they are entirely ineffective. Independent studies have their effectiveness rate at less than 20%, and fewer than 10% of workers qualify. One thing that I think is really irresponsible is imagining that it’s somehow realistic to retrain hundreds of thousands of people without any evidence to that effect.

Ahsan: Why do you believe the Democrats lost in the previous election?

Yang: I think that there are a few failings of the Democratic Party. The reason Donald Trump is our president is because the Democratic Party stopped truly focusing on how to improve the lives of the average working American. The manufacturing sector used to be a core Democratic base, but over the last number of decades, unions have gotten weaker and weaker. Now they’ve lost half their membership, and the Democrats have shifted their focus from trying to better the lives of American working class to other concerns. I do believe that universal basic income is the future of the Democratic Party.

Ahsan: Do you find that the social stigma attached to universal basic income in the United States is changing?

Yang: I think that the recognition is growing all the time that our previous framing of these sorts of solutions is just archaic. We lost 4 million manufacturing jobs in 2016, and the disappearance of other job categories because of automation is indisputable.

People think of capitalism and socialism as diametrically opposed, and capitalism won, but the truth is that we need to evolve our system and integrate the best aspects of both, ideally.

Ahsan: Will employers still feel compelled to pay a proper wage to their workers with a basic income? Do you think it will improve the workers’ bargaining power?

Yang: It will have different effects on different lines of work. There are certain forms of work that people really like to do, like being an artist, that will probably be very popular with basic income. And there are very unpleasant jobs that you will probably have to pay more to do.

One thing that I am confident of is that worker freedom and bargaining power will go up in a world where people are receiving basic income because the fear of being indigent on the street will have disappeared. An employer truly trying to exploit workers would struggle more than they are right now to get people to work for them.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.